“Everyone has a Right to the Kids Except their Mother”: On Women Fighting for the Custody of Their Children

11 Mar 2024

After a husband passes away, mothers can lose access to their children, if they don’t accept to live at their in-laws’ house or under their control. The stories of widows who lost -or nearly lost- access to their sons and daughters after discovering that the family, tribe, and clergy have more rights to their children than they do.

If it were not for the violence and mistreatment that she faced, Nagham would not have moved far away from her children. unable to share their joys and support them in times of hardship.

Nagham (forty-nine years old) lost her husband in 2009 after he fell ill and has been in a battle with her in-laws for custody of their children ever since. The in-laws did not want her to continue living with them in their home, but still wanted to keep the children. So, they started planning how to force Nagham to leave without her kids.

The plan was to mistreat her and physically and verbally abuse her for the flimsiest of reasons, making her life with them a living hell, and forcing her to abandon everything and leave. Eventually the plan worked, and Nagham decided to return to her own family home, leaving her children in the custody of their paternal grandfather.

One of the factors that forced Nagham to make that decision was that the children asked her to leave and to let them stay at their grandfather’s house. This is because they were very frustrated by daily problems and arguments. Her eldest son was sixteen then, and he has two brothers and a sister who were a few years younger.

Another reason she swallowed the bitter pill of leaving, was her family’s living conditions, since they lived in a small house and would not have been able to afford putting up both her and her kids. Her in-laws were more well-off.

Ultimately, she did not have money to pay for lawyers, her family refused to host her with the children due to the difficult conditions there, and her kids chose to live at their grandfather’s house. This prevented her from seeking legal recourse to gain custody.

Furthermore, her husband had money, real estate, and cars, which she received nothing from as her in-laws made her sign a waiver claiming no right to her husband’s property after she moved to her family’s house. “They told me they wanted to buy new property and furniture instead of the old ones, and then they would bring me back to live with them next to my kids”, Nagham told Jummar.

She was tricked into signing the waiver in front of a notary but received nothing in return. When she went to a lawyer, he informed her that she no longer had a right to any inheritance from her husband after signing the waiver.

Nagham was not comfortable in her family’s home, so she rented a small house and moved there alone. She receives a monthly government subsidy of 123 thousand dinars (about 80 US Dollars) from a governmental social security department, a pittance that does not meet the most basic needs.

“I have to endure the heat of Iraqi summers – that no one else can – because I can’t afford to register for the local generator”, she tells us.

Nagham has not seen her children in two years. Her eldest son even got married without letting her know, and her daughter was forced to marry at the age of fifteen against her will. It was out of Nagham’s hands.

Between two bitter choices

Azhar (33 years old) lost her husband in a car accident in 2020. She had three kids with him, the eldest of whom was nine years old when her husband passed. She then remained at her in-laws’ house along with her children, but the sense of discomfort prevailed due to the presence of her brothers-in-law – both married and single – which caused pressure from their family whose customs did not allow such a living arrangement.

A few months after her husband’s death, her husband’s family began pressuring her to marry one of his brothers, which she refused since he was like a brother to her. They then suggested it to be merely a paper marriage – a marriage in name only – for her to stay with the kids in their house, but she insisted on rejecting living in such a situation.

Following this, her father-in-law threatened to take the children by force, which divided the family between those who were for and others against. However, the grandfather stood his ground, claiming that he did not want his grandchildren to be raised by a stranger in case the mother decided to remarry.

Eventually, the children were taken from her, and she was kicked out of her in-laws’ home, despite her youngest being only three years old. “My kids stayed at their grandfathers for a long time while I was denied seeing them”, she told Jummar. Azhar suffered a stroke due to her severe anxiety and depression, the effects of which she still suffers from.After an intervention from the local tribe, the grandfather agreed to return the children to her on the condition that he would reclaim them if she ever decided to remarry.

Even after her children returned, her in-laws still exerted control over her life while she lived at her family home. For instance, they opposed her pursuing her studies or working, claiming that it would distract her from devoting herself to raising the children of their deceased son. Even traveling with the kids is not permitted without the grandfather’s approval.

According to Azhar, the grandfather often asks her son to look through her phone and find out who she talks to, in an attempt to find proof that she has damaged her reputation so he can retake the children from her.

Azhar knows that her father-in-law’s actions are illegal, but she is also at the same time aware that tribal agreements are sometimes stronger than the law. Thus, she did not resort to the law after the matter became a tribal issue.

A regretful marriage

After a six-year marriage that produced a daughter and a son, Maysoun lost her husband. Her daughter is now four-year-old and her son is one and a half. She then moved to live at her husband’s family’s house after his passing, but her in-laws started pressuring her to marry one of her brothers-in-law, under the pretext of it being the only way to keep her children, as they would take them if she married another man.

She was given the choice of either becoming a second wife to her husband’s married brother who had children, or marrying her widower brother-in-law who was twenty years older than her and had three kids. She was only nineteen at the time.

Fearing that she would lose her two children, Maysoun agreed to marry the widower. At the time, she did not know anything about lawsuits and the possibility of keeping her two children by court order, without choosing to marry the brother of her deceased husband. Additionally, she thought he might be a good father for them, and she was able to accept the idea of marrying him as he lived in the Wasit governorate – southeast of Baghdad – and barely visited them.

However, it turned out to be an unhappy marriage. “If I was as mature as I am now, I would not have accepted this marriage”, she told Jummar.

She still regrets her decision to this day, since her life with her husband’s brother was not a happy one. Besides her difficulty in living with the age difference, his children did not welcome her in their father’s house, leading to jealousy between the family members.

Getting your own house is forbidden

Despite her husband’s death in 2020, Iman (38-year-old) still lives at her in-laws’ house in the city of Samawah, the centre of Al-Muthanna Governorate, to be able to keep her three daughters.

When her husband died, his family told her that she had no right to live in a separate house with her daughters, since there is no male living with them. She already owned a house that she could not move into. Iman reluctantly agreed to stay at her husband’s family’s house – who was also her cousin – after coming into an agreement with her family in this regard.

“I know they cannot legally take my daughters from me if I move into my own private house, but there are traditions and customs. I didn’t want to oppose my daughters’ uncles’s wishes for us to live with them”, she tells Jummar.

Iman now receives a monthly government subsidy of 320 thousand dinars (about 245 US dollars) from the social welfare department, which cannot fulfill her and her daughters’ needs, who are school students. This is why she had to work as a tailor to earn extra income.

Customs are enforced (rather than the law)

Legal expert Bushra Al-Obaidi says that several conditions must be met by the custodial parent; she must be “sane, honest, able to protect and care for the child in custody, and well respected”. In case the mother does not meet all or some of these conditions, the court can decide to give custody to whomever it deems fit among the child’s closest relatives.

Al-Obaidi acknowledges, however, that the court is sometimes biased towards social customs. She points out that, according to tribal custom, custody is given to the deceased husband’s family, and if the widow wishes to keep her children, she is forced to not remarry or marry one of her husband’s brothers.

“This is very humiliating and insulting to the widow, who may be abstaining from marriage out of loyalty to her husband, but custom does not consider this”, Al-Obaidi told Jummar.

Al-Obaidi attributes the fact that widows who face such pressures do not file complaints due to the financial cost of the legal cases and the fear that most women have of even entering police stations. The legal expert emphasises that Iraqi law grants full custody to the widowed mother and that no one holds the right to violate that law by imposing any other standard. Still, the pressures and conditions imposed on widows stem from customs and traditions.

The tribe comes before the law

In tribal custom, the widow has the right to custody of her children if she does not intend to remarry, according to Nafie Kazar, a tribal sheikh. According to Kazar however, if the widow decides to remarry then custody goes to the paternal grandfather or uncles, based on a tribal rule that “rejects their grandchildren being raised by a stranger, especially if the new husband belongs to another tribe”.

Kazar adds that there are many successful marriages between widows and their brothers-in-law, but still stresses that such marriages should never be carried out by forcing or exploiting women.

He points out that the tribe respects any judicial decisions if the widow seeks out the court and is granted a legal right of custody under all circumstances. Still, he adds that most people resort to tribal solutions in such cases.

“Matters are not solved easily in courts, while the tribe solves any problem in one deliberative meeting. If an agreement is made by the tribe, it is impossible to revoke it and seek out the court”, Kazar tells Jummar.

Kazim Al-Ziyadi, a tribal sheikh, shares a similar opinion regarding the rights of paternal grandparents to custody. He says, “If the widowed wife remarries, neither her the family nor her new husbandcan retain custody of the children”.

This strictness becomes more severe with girls, as they are considered to be “men’s honour” and must be raised according to the traditions and customs of the husband’s family and tribe.

If the widow decides to remarry, she is allowed to meet her children once a week or once a month if they are over five years old. I they are younger, then the tribal community can sometimes consider keeping them with the mother, according to Al-Ziyadi. He believes that customs are important even to the judges, “In some cases, they say that the issue is better solved according to the judgement of the tribe” as they prefer putting the legal solution second. Al-Ziyadi continues, “Even if a judicial decision is issued, the tribe’s intervention remains more binding”.

What does Religion Say?

Religious law (Shariah) has more to say regarding the guardianship of fatherless children. Ali Al-Sharifi, a cleric (Imam), says that Shariah law stipulates that guardianship is granted to the paternal grandfather when the father dies. If the grandfather is deceased, it is then up to the rightful ruler, who is the supreme authority, to decide who the guardian shall be. He clarifies that guardianship is related to managing the inherited money and property, while custody is legally granted to the mother even without the grandfather’s consent, and whether the mother remarries or not.

Al-Sharifi points out that Iraqi society is governed by customs, not religion, and accuses some clerics of favoring customs over Shariah law in issuing illegitimate rulings to satisfy particular communities.

Female lawyers for the widows

According to human rights activist Mona Jaafar, head of the Widows Training and Development Center (WTDC) in Baghdad, the root cause of the problem is related to tribal dominance. Jafaar told Jummar that even if the widow resorted to the police, they would refer the issue to an authorised person from her tribe.

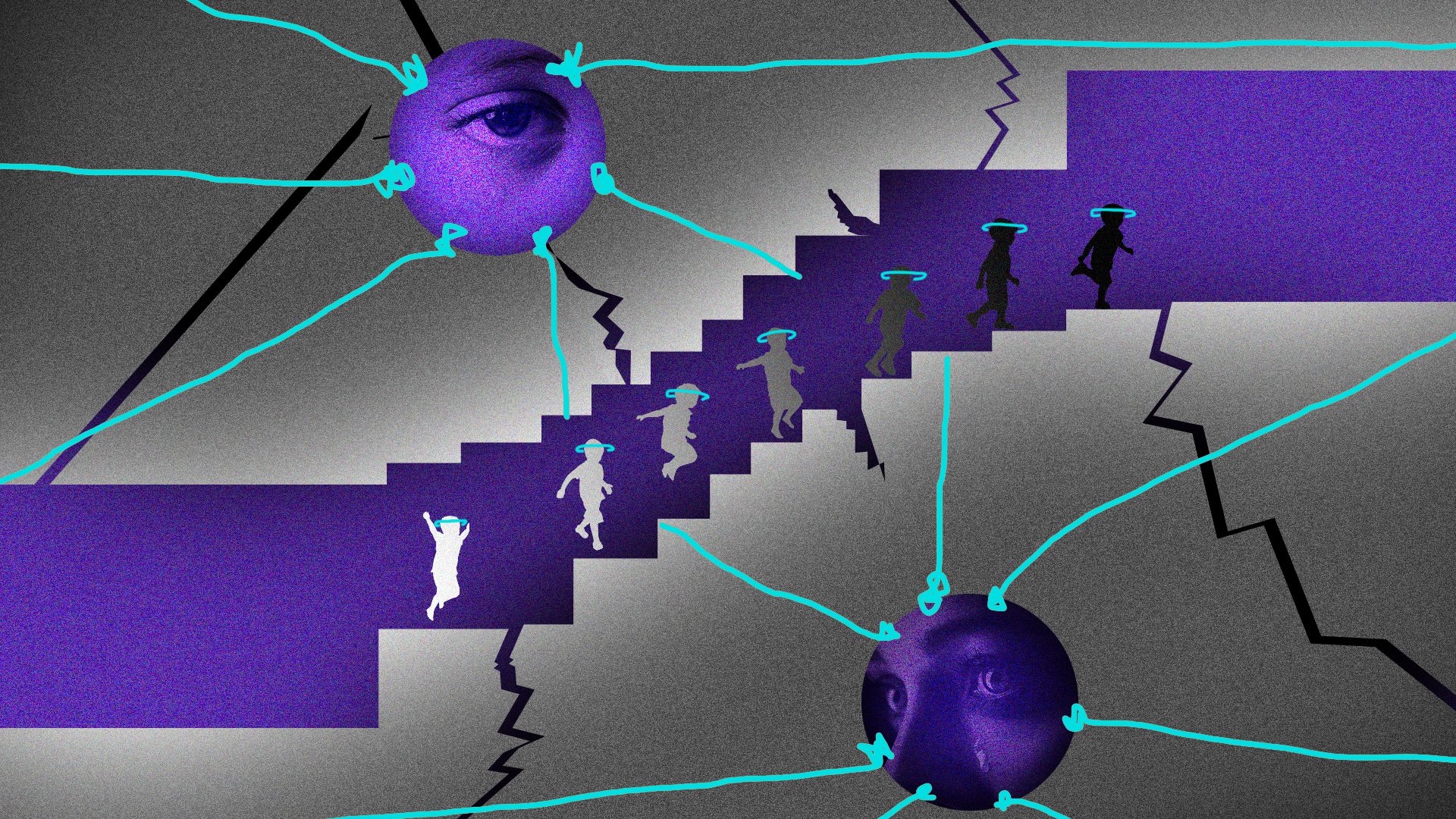

Infographic 4: She has not seen her children in two years. Her eldest son even got married without informing her, and her daughter was forced to marry at the age of 15 against her will

This sometimes is due to a marriage not being registered in court, which results in the lack of legal documents proving the identity of the children’s father. Jaafar adds that her organisation provides female lawyers to represent widows to government agencies to prove their right to child custody and obtain social welfare subsidies.

Nagham’s hopes

All Nagham can cling to for her life to change for the better – and for her children to change their behavior towards her – is hope. The longer her children are away at their grandfather’s house, the less they want to visit or contact her since that contact triggers mistreatment and violence from their uncles. She also hopes to live in a decent house, get a job, and reunite with her children who she does not blame, since, as she puts it, “life forced them to abandon their mother so that they could live in peace”.

Read More

“His gaze was intrusive; it pierced my soul”: On the Struggles of Divorced Women in Navigating Courts and Governmental Institutions

“She Brought a Fatwa from Khamenei and Al-Azhar, But It Went Nowhere”: The Struggles of Trans People in the Iraqi Health Sector

Iraqi Prisoners Blackmailed to Pay To Obtain Release Papers After Completing Their Sentence

“We Have to Make a Living Somehow”: Women Working Hard under the Heat of Dhi Qar

If it were not for the violence and mistreatment that she faced, Nagham would not have moved far away from her children. unable to share their joys and support them in times of hardship.

Nagham (forty-nine years old) lost her husband in 2009 after he fell ill and has been in a battle with her in-laws for custody of their children ever since. The in-laws did not want her to continue living with them in their home, but still wanted to keep the children. So, they started planning how to force Nagham to leave without her kids.

The plan was to mistreat her and physically and verbally abuse her for the flimsiest of reasons, making her life with them a living hell, and forcing her to abandon everything and leave. Eventually the plan worked, and Nagham decided to return to her own family home, leaving her children in the custody of their paternal grandfather.

One of the factors that forced Nagham to make that decision was that the children asked her to leave and to let them stay at their grandfather’s house. This is because they were very frustrated by daily problems and arguments. Her eldest son was sixteen then, and he has two brothers and a sister who were a few years younger.

Another reason she swallowed the bitter pill of leaving, was her family’s living conditions, since they lived in a small house and would not have been able to afford putting up both her and her kids. Her in-laws were more well-off.

Ultimately, she did not have money to pay for lawyers, her family refused to host her with the children due to the difficult conditions there, and her kids chose to live at their grandfather’s house. This prevented her from seeking legal recourse to gain custody.

Furthermore, her husband had money, real estate, and cars, which she received nothing from as her in-laws made her sign a waiver claiming no right to her husband’s property after she moved to her family’s house. “They told me they wanted to buy new property and furniture instead of the old ones, and then they would bring me back to live with them next to my kids”, Nagham told Jummar.

She was tricked into signing the waiver in front of a notary but received nothing in return. When she went to a lawyer, he informed her that she no longer had a right to any inheritance from her husband after signing the waiver.

Nagham was not comfortable in her family’s home, so she rented a small house and moved there alone. She receives a monthly government subsidy of 123 thousand dinars (about 80 US Dollars) from a governmental social security department, a pittance that does not meet the most basic needs.

“I have to endure the heat of Iraqi summers – that no one else can – because I can’t afford to register for the local generator”, she tells us.

Nagham has not seen her children in two years. Her eldest son even got married without letting her know, and her daughter was forced to marry at the age of fifteen against her will. It was out of Nagham’s hands.

Between two bitter choices

Azhar (33 years old) lost her husband in a car accident in 2020. She had three kids with him, the eldest of whom was nine years old when her husband passed. She then remained at her in-laws’ house along with her children, but the sense of discomfort prevailed due to the presence of her brothers-in-law – both married and single – which caused pressure from their family whose customs did not allow such a living arrangement.

A few months after her husband’s death, her husband’s family began pressuring her to marry one of his brothers, which she refused since he was like a brother to her. They then suggested it to be merely a paper marriage – a marriage in name only – for her to stay with the kids in their house, but she insisted on rejecting living in such a situation.

Following this, her father-in-law threatened to take the children by force, which divided the family between those who were for and others against. However, the grandfather stood his ground, claiming that he did not want his grandchildren to be raised by a stranger in case the mother decided to remarry.

Eventually, the children were taken from her, and she was kicked out of her in-laws’ home, despite her youngest being only three years old. “My kids stayed at their grandfathers for a long time while I was denied seeing them”, she told Jummar. Azhar suffered a stroke due to her severe anxiety and depression, the effects of which she still suffers from.After an intervention from the local tribe, the grandfather agreed to return the children to her on the condition that he would reclaim them if she ever decided to remarry.

Even after her children returned, her in-laws still exerted control over her life while she lived at her family home. For instance, they opposed her pursuing her studies or working, claiming that it would distract her from devoting herself to raising the children of their deceased son. Even traveling with the kids is not permitted without the grandfather’s approval.

According to Azhar, the grandfather often asks her son to look through her phone and find out who she talks to, in an attempt to find proof that she has damaged her reputation so he can retake the children from her.

Azhar knows that her father-in-law’s actions are illegal, but she is also at the same time aware that tribal agreements are sometimes stronger than the law. Thus, she did not resort to the law after the matter became a tribal issue.

A regretful marriage

After a six-year marriage that produced a daughter and a son, Maysoun lost her husband. Her daughter is now four-year-old and her son is one and a half. She then moved to live at her husband’s family’s house after his passing, but her in-laws started pressuring her to marry one of her brothers-in-law, under the pretext of it being the only way to keep her children, as they would take them if she married another man.

She was given the choice of either becoming a second wife to her husband’s married brother who had children, or marrying her widower brother-in-law who was twenty years older than her and had three kids. She was only nineteen at the time.

Fearing that she would lose her two children, Maysoun agreed to marry the widower. At the time, she did not know anything about lawsuits and the possibility of keeping her two children by court order, without choosing to marry the brother of her deceased husband. Additionally, she thought he might be a good father for them, and she was able to accept the idea of marrying him as he lived in the Wasit governorate – southeast of Baghdad – and barely visited them.

However, it turned out to be an unhappy marriage. “If I was as mature as I am now, I would not have accepted this marriage”, she told Jummar.

She still regrets her decision to this day, since her life with her husband’s brother was not a happy one. Besides her difficulty in living with the age difference, his children did not welcome her in their father’s house, leading to jealousy between the family members.

Getting your own house is forbidden

Despite her husband’s death in 2020, Iman (38-year-old) still lives at her in-laws’ house in the city of Samawah, the centre of Al-Muthanna Governorate, to be able to keep her three daughters.

When her husband died, his family told her that she had no right to live in a separate house with her daughters, since there is no male living with them. She already owned a house that she could not move into. Iman reluctantly agreed to stay at her husband’s family’s house – who was also her cousin – after coming into an agreement with her family in this regard.

“I know they cannot legally take my daughters from me if I move into my own private house, but there are traditions and customs. I didn’t want to oppose my daughters’ uncles’s wishes for us to live with them”, she tells Jummar.

Iman now receives a monthly government subsidy of 320 thousand dinars (about 245 US dollars) from the social welfare department, which cannot fulfill her and her daughters’ needs, who are school students. This is why she had to work as a tailor to earn extra income.

Customs are enforced (rather than the law)

Legal expert Bushra Al-Obaidi says that several conditions must be met by the custodial parent; she must be “sane, honest, able to protect and care for the child in custody, and well respected”. In case the mother does not meet all or some of these conditions, the court can decide to give custody to whomever it deems fit among the child’s closest relatives.

Al-Obaidi acknowledges, however, that the court is sometimes biased towards social customs. She points out that, according to tribal custom, custody is given to the deceased husband’s family, and if the widow wishes to keep her children, she is forced to not remarry or marry one of her husband’s brothers.

“This is very humiliating and insulting to the widow, who may be abstaining from marriage out of loyalty to her husband, but custom does not consider this”, Al-Obaidi told Jummar.

Al-Obaidi attributes the fact that widows who face such pressures do not file complaints due to the financial cost of the legal cases and the fear that most women have of even entering police stations. The legal expert emphasises that Iraqi law grants full custody to the widowed mother and that no one holds the right to violate that law by imposing any other standard. Still, the pressures and conditions imposed on widows stem from customs and traditions.

The tribe comes before the law

In tribal custom, the widow has the right to custody of her children if she does not intend to remarry, according to Nafie Kazar, a tribal sheikh. According to Kazar however, if the widow decides to remarry then custody goes to the paternal grandfather or uncles, based on a tribal rule that “rejects their grandchildren being raised by a stranger, especially if the new husband belongs to another tribe”.

Kazar adds that there are many successful marriages between widows and their brothers-in-law, but still stresses that such marriages should never be carried out by forcing or exploiting women.

He points out that the tribe respects any judicial decisions if the widow seeks out the court and is granted a legal right of custody under all circumstances. Still, he adds that most people resort to tribal solutions in such cases.

“Matters are not solved easily in courts, while the tribe solves any problem in one deliberative meeting. If an agreement is made by the tribe, it is impossible to revoke it and seek out the court”, Kazar tells Jummar.

Kazim Al-Ziyadi, a tribal sheikh, shares a similar opinion regarding the rights of paternal grandparents to custody. He says, “If the widowed wife remarries, neither her the family nor her new husbandcan retain custody of the children”.

This strictness becomes more severe with girls, as they are considered to be “men’s honour” and must be raised according to the traditions and customs of the husband’s family and tribe.

If the widow decides to remarry, she is allowed to meet her children once a week or once a month if they are over five years old. I they are younger, then the tribal community can sometimes consider keeping them with the mother, according to Al-Ziyadi. He believes that customs are important even to the judges, “In some cases, they say that the issue is better solved according to the judgement of the tribe” as they prefer putting the legal solution second. Al-Ziyadi continues, “Even if a judicial decision is issued, the tribe’s intervention remains more binding”.

What does Religion Say?

Religious law (Shariah) has more to say regarding the guardianship of fatherless children. Ali Al-Sharifi, a cleric (Imam), says that Shariah law stipulates that guardianship is granted to the paternal grandfather when the father dies. If the grandfather is deceased, it is then up to the rightful ruler, who is the supreme authority, to decide who the guardian shall be. He clarifies that guardianship is related to managing the inherited money and property, while custody is legally granted to the mother even without the grandfather’s consent, and whether the mother remarries or not.

Al-Sharifi points out that Iraqi society is governed by customs, not religion, and accuses some clerics of favoring customs over Shariah law in issuing illegitimate rulings to satisfy particular communities.

Female lawyers for the widows

According to human rights activist Mona Jaafar, head of the Widows Training and Development Center (WTDC) in Baghdad, the root cause of the problem is related to tribal dominance. Jafaar told Jummar that even if the widow resorted to the police, they would refer the issue to an authorised person from her tribe.

Infographic 4: She has not seen her children in two years. Her eldest son even got married without informing her, and her daughter was forced to marry at the age of 15 against her will

This sometimes is due to a marriage not being registered in court, which results in the lack of legal documents proving the identity of the children’s father. Jaafar adds that her organisation provides female lawyers to represent widows to government agencies to prove their right to child custody and obtain social welfare subsidies.

Nagham’s hopes

All Nagham can cling to for her life to change for the better – and for her children to change their behavior towards her – is hope. The longer her children are away at their grandfather’s house, the less they want to visit or contact her since that contact triggers mistreatment and violence from their uncles. She also hopes to live in a decent house, get a job, and reunite with her children who she does not blame, since, as she puts it, “life forced them to abandon their mother so that they could live in peace”.