“We Have to Make a Living Somehow”: Women Working Hard under the Heat of Dhi Qar

19 Sep 2023

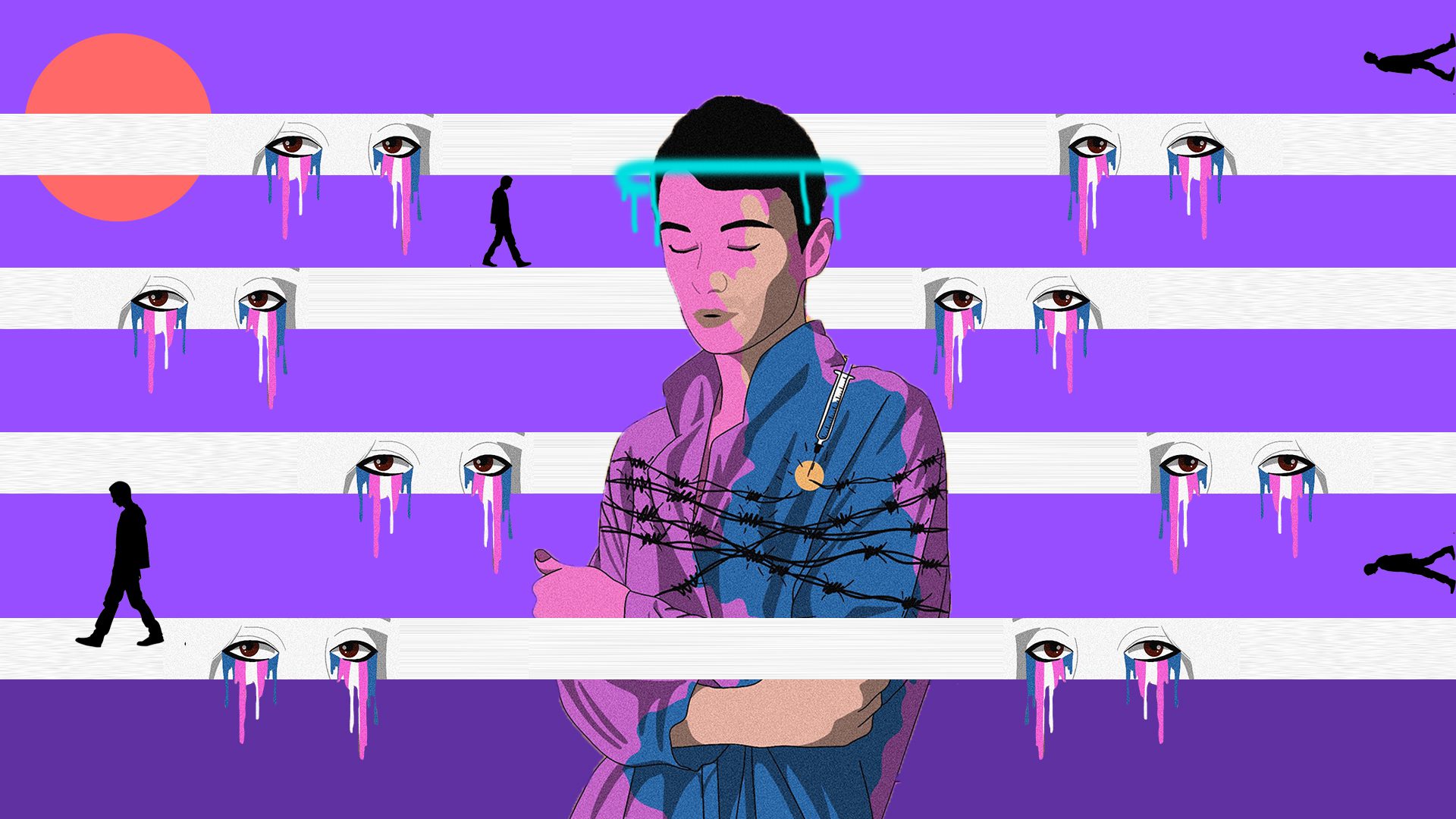

Millions of elderly people in Iraq suffer from the rising temperatures, but the suffering of women working under the sun in Dhi Qar is beyond imagination. This is the story of Umm Karar, Umm Jassim, and the “empowerment” they are waiting for to maintain a decent livelihood and a sense of well-being under the sweltering temperatures.

Al-Haraj market, in the centre of Nasiriyah, where dozens of women and men occupy a deserted, open field during summer and winter. One of them is Umm Karar, who has been buying and selling second-hand clothes for twenty years.

Her house is an hour away from the market, so she goes out daily at seven in the morning to reach her spot where she spreads a carpet under her stall and sits in the shade of an abandoned porch while dealing with her customers. The woman, who is in her fifties, then leaves for home at eleven, as the morning hours are more bearable in the heat.

“It is sweltering, but thank God for everything. God knows our situation, and he tries us according to our capabilities”, says Umm Karar, despite having diabetes and hypertension, which are affected by the heat. High temperatures lead to physiological disorders, mainly high blood pressure and allergies, including skin irritation and respiratory disorders.

Such suffering is the fate of millions of elderly people in Iraq, who are affected dramatically by high temperatures. However, working outside in the sun, especially in Dhi Qar, worsens it.

Dhi Qar is located 400 kilometres south of the capital, Baghdad, and it is one of the governorates most affected by climate change due to the water scarcity in the rivers feeding it, as well as the dusty monsoon winds, and, of course, the high temperatures. The Meteorological Department records a daily temperature exceeding forty-nine degrees Celsius during summer outdoors, while it reaches fifty-five degrees Celsius in enclosed spaces and streets, according to Ahmad Kareem, Assistant Director of the department.

Al-Haraj market is among the hottest areas. Most women vendors there wear black clothes, making them more susceptible to the heat as black absorbs light rather than reflecting it. In addition, there are risks such as skin diseases, including cancer.

“The sun kills me”

Under a small umbrella, Umm Jassim sets up a stall selling fish on a dusty road in the market under the blazing heat. The woman, also in her fifties, complains of constant headaches due to the sun’s heat. She points under her stall with her stiff, dry hands and their bulging veins and shows her medicine strips, which she hides in the shade, “It is the demands of life, and I have a big family. I just took two pills”, she said.

Umm Jassim cannot bear July’s extreme heat. The headache she gets from the sun causes her severe pain and exhaustion, sometimes forcing her to stay home for up to ten days after a working day. “The other day I came to sell, the following day, I stayed home. The sun and (the passing) cars killed me, I could not bear it”.

The incidence of heart strokes has increased. This condition leads to severe headaches, blurred vision, extreme fatigue and exhaustion, and loss of fluids due to frequent vomiting and diarrhoea, causing severe dehydration. This happens especially to older people, children, and the poor.

Many of the women working in Al-Haraj market are in their forties to late sixties, a stage in their life in which they suffer from hot flashes due to the menopause. The rising temperature of their bodies causes uncomfortable symptoms such as a sense of suffocation, shortness of breath, fatigue and headaches, which are exacerbated by being under the sun.

Generally, older people are more affected by high temperatures due to their bodies’ reduced ability to sweat and perform metabolic processes. Dr Hussein Riyad, Director of the Public Health Department in Dhi Qar, has noticed the increase in the number of older people visiting health centres in the summer. Still, he is aware that financial difficulties force many elderly women to work in these conditions.

The sun is not the only cause of harm to vendors in Al-Haraj market, as a landfill borders the market. Additionally, the market is not set up for this type of work, as it is totally neglected by the government, similar to other markets in the city of Nasiriyah -the centre of Dhi Qar Governorate- that lack proper health and environmental working conditions. Thus, vendors cannot escape the sun except by taking shelter under small umbrellas or rags set up on poles.

These conditions reflect the neglect of a segment of workers who make a living by selling vegetables, meat, clothes, and dairy all in one place. Alaa Naji, Director of the Women’s Empowerment Department in the governorate, believes that these conditions can be improved with a little care from the state or civil society institutions.

Improving the condition of markets is considered in the public interest, the benefit of which is not limited to women, despite being the most affected, but to all vendors and buyers as it guarantees the safety of the products they buy.

Empowering women in the markets, too

The few days Umm Jassim works each month provide for her family’s minimum needs, as the welfare payment of 170 thousand dinars, which she receives -after the deduction of five thousand by the payment office- barely covers basic daily expenses. “What can I possibly buy with it? It can only get tea, water, cigarettes, and falafel wraps. Here they are”, she says.

Dhi Qar is an oil-producing governorate, yet it records high rates of poverty and deprivation compared to other governorates, especially among women. The Human Rights Department in the governorate describes the situation of women working in this informal and unprotected economy as very tragic, according to Dakhel Al-Mushrafawi, Director of the department, who stressed the necessity of conducting an accurate government survey that determines the percentage of families below the poverty line in Dhi Qar, in addition to improving their conditions with actual plans and programmes.

However, Al-Mushrafawi also warned against the reliance on humanitarian aid and specific support grants, as they are not sufficient nor inclusive, especially for women. Particularly as the government in the current period does not have the economic prosperity required to support low-income families, he explained.

According to him, the inclusion of women in the Social Welfare Act is subject to many regulations and procedures, depriving many women of benefiting from support because they have a breadwinner or another programme beneficiary within the family. Moreover, he added that the amounts they receive are insufficient to meet general needs because of high prices, rents, and fees of various services.

Umm Karar tells us that she has worked as a vendor of different items over the past twenty years, from wooden furniture to refrigerators and clothes, to name but a few. Although she described her work as a struggle, she was used to it and could not give it up and stay home.

Naji, the Director of Dhi Qar’s Women’s Empowerment Department, points out that these women are associated with this type of work because they have mastered it after practising it for many years, especially older women who are less able to learn a new profession such as sewing or dairy farming. They also do not want to do so.

However, habit is not the only thing that motivates Umm Karar to work, as work provides her with a minimum decent living. She describes her earnings as a daily livelihood, “It is enough for one day’s groceries, and that’s it”, she says. Despite receiving her husband’s retirement pension, who died eleven years ago, it is only enough for monthly living needs. It does not cover contingency expenses, such as when she had to get a loan of one million dinars (around 760 US dollars), which she needed to pay for surgery for one of her daughters.

Therefore, it is not helpful to try changing the nature of these women’s work by including them in women’s economic empowerment programmes, such as enrolling them on training courses for specific professions like sewing and dairy farming, Naji says. Instead, it would be more beneficial if official authorities improved the already-existing local markets with proper infrastructure and equipped stalls to provide vendors with humane and healthy conditions in which they can work.

The women’s empowerment programme, which the central government works on in cooperation with local governments through its various departments, is plagued by ineffective procedures. This has led to the involvement of international organisations to empower market and street vendors who are women by establishing proper stalls. However, the government’s bureaucratic nature is the main obstacle in providing a suitable foundation for such projects.

The conditions of working women in Dhi Qar lack many elements of healthcare and social and economic welfare, forcing many women to work on the streets and pavements under the blazing sun during the peak of the summer heat, which locals call “the days of dates cooking” as the intense heat contributes to the ripening of the date harvest. However, all the ideas and programmes to support these women are, regrettably, yet to ripen.

Read More

“His gaze was intrusive; it pierced my soul”: On the Struggles of Divorced Women in Navigating Courts and Governmental Institutions

“She Brought a Fatwa from Khamenei and Al-Azhar, But It Went Nowhere”: The Struggles of Trans People in the Iraqi Health Sector

“Everyone has a Right to the Kids Except their Mother”: On Women Fighting for the Custody of Their Children

Iraqi Prisoners Blackmailed to Pay To Obtain Release Papers After Completing Their Sentence

Al-Haraj market, in the centre of Nasiriyah, where dozens of women and men occupy a deserted, open field during summer and winter. One of them is Umm Karar, who has been buying and selling second-hand clothes for twenty years.

Her house is an hour away from the market, so she goes out daily at seven in the morning to reach her spot where she spreads a carpet under her stall and sits in the shade of an abandoned porch while dealing with her customers. The woman, who is in her fifties, then leaves for home at eleven, as the morning hours are more bearable in the heat.

“It is sweltering, but thank God for everything. God knows our situation, and he tries us according to our capabilities”, says Umm Karar, despite having diabetes and hypertension, which are affected by the heat. High temperatures lead to physiological disorders, mainly high blood pressure and allergies, including skin irritation and respiratory disorders.

Such suffering is the fate of millions of elderly people in Iraq, who are affected dramatically by high temperatures. However, working outside in the sun, especially in Dhi Qar, worsens it.

Dhi Qar is located 400 kilometres south of the capital, Baghdad, and it is one of the governorates most affected by climate change due to the water scarcity in the rivers feeding it, as well as the dusty monsoon winds, and, of course, the high temperatures. The Meteorological Department records a daily temperature exceeding forty-nine degrees Celsius during summer outdoors, while it reaches fifty-five degrees Celsius in enclosed spaces and streets, according to Ahmad Kareem, Assistant Director of the department.

Al-Haraj market is among the hottest areas. Most women vendors there wear black clothes, making them more susceptible to the heat as black absorbs light rather than reflecting it. In addition, there are risks such as skin diseases, including cancer.

“The sun kills me”

Under a small umbrella, Umm Jassim sets up a stall selling fish on a dusty road in the market under the blazing heat. The woman, also in her fifties, complains of constant headaches due to the sun’s heat. She points under her stall with her stiff, dry hands and their bulging veins and shows her medicine strips, which she hides in the shade, “It is the demands of life, and I have a big family. I just took two pills”, she said.

Umm Jassim cannot bear July’s extreme heat. The headache she gets from the sun causes her severe pain and exhaustion, sometimes forcing her to stay home for up to ten days after a working day. “The other day I came to sell, the following day, I stayed home. The sun and (the passing) cars killed me, I could not bear it”.

The incidence of heart strokes has increased. This condition leads to severe headaches, blurred vision, extreme fatigue and exhaustion, and loss of fluids due to frequent vomiting and diarrhoea, causing severe dehydration. This happens especially to older people, children, and the poor.

Many of the women working in Al-Haraj market are in their forties to late sixties, a stage in their life in which they suffer from hot flashes due to the menopause. The rising temperature of their bodies causes uncomfortable symptoms such as a sense of suffocation, shortness of breath, fatigue and headaches, which are exacerbated by being under the sun.

Generally, older people are more affected by high temperatures due to their bodies’ reduced ability to sweat and perform metabolic processes. Dr Hussein Riyad, Director of the Public Health Department in Dhi Qar, has noticed the increase in the number of older people visiting health centres in the summer. Still, he is aware that financial difficulties force many elderly women to work in these conditions.

The sun is not the only cause of harm to vendors in Al-Haraj market, as a landfill borders the market. Additionally, the market is not set up for this type of work, as it is totally neglected by the government, similar to other markets in the city of Nasiriyah -the centre of Dhi Qar Governorate- that lack proper health and environmental working conditions. Thus, vendors cannot escape the sun except by taking shelter under small umbrellas or rags set up on poles.

These conditions reflect the neglect of a segment of workers who make a living by selling vegetables, meat, clothes, and dairy all in one place. Alaa Naji, Director of the Women’s Empowerment Department in the governorate, believes that these conditions can be improved with a little care from the state or civil society institutions.

Improving the condition of markets is considered in the public interest, the benefit of which is not limited to women, despite being the most affected, but to all vendors and buyers as it guarantees the safety of the products they buy.

Empowering women in the markets, too

The few days Umm Jassim works each month provide for her family’s minimum needs, as the welfare payment of 170 thousand dinars, which she receives -after the deduction of five thousand by the payment office- barely covers basic daily expenses. “What can I possibly buy with it? It can only get tea, water, cigarettes, and falafel wraps. Here they are”, she says.

Dhi Qar is an oil-producing governorate, yet it records high rates of poverty and deprivation compared to other governorates, especially among women. The Human Rights Department in the governorate describes the situation of women working in this informal and unprotected economy as very tragic, according to Dakhel Al-Mushrafawi, Director of the department, who stressed the necessity of conducting an accurate government survey that determines the percentage of families below the poverty line in Dhi Qar, in addition to improving their conditions with actual plans and programmes.

However, Al-Mushrafawi also warned against the reliance on humanitarian aid and specific support grants, as they are not sufficient nor inclusive, especially for women. Particularly as the government in the current period does not have the economic prosperity required to support low-income families, he explained.

According to him, the inclusion of women in the Social Welfare Act is subject to many regulations and procedures, depriving many women of benefiting from support because they have a breadwinner or another programme beneficiary within the family. Moreover, he added that the amounts they receive are insufficient to meet general needs because of high prices, rents, and fees of various services.

Umm Karar tells us that she has worked as a vendor of different items over the past twenty years, from wooden furniture to refrigerators and clothes, to name but a few. Although she described her work as a struggle, she was used to it and could not give it up and stay home.

Naji, the Director of Dhi Qar’s Women’s Empowerment Department, points out that these women are associated with this type of work because they have mastered it after practising it for many years, especially older women who are less able to learn a new profession such as sewing or dairy farming. They also do not want to do so.

However, habit is not the only thing that motivates Umm Karar to work, as work provides her with a minimum decent living. She describes her earnings as a daily livelihood, “It is enough for one day’s groceries, and that’s it”, she says. Despite receiving her husband’s retirement pension, who died eleven years ago, it is only enough for monthly living needs. It does not cover contingency expenses, such as when she had to get a loan of one million dinars (around 760 US dollars), which she needed to pay for surgery for one of her daughters.

Therefore, it is not helpful to try changing the nature of these women’s work by including them in women’s economic empowerment programmes, such as enrolling them on training courses for specific professions like sewing and dairy farming, Naji says. Instead, it would be more beneficial if official authorities improved the already-existing local markets with proper infrastructure and equipped stalls to provide vendors with humane and healthy conditions in which they can work.

The women’s empowerment programme, which the central government works on in cooperation with local governments through its various departments, is plagued by ineffective procedures. This has led to the involvement of international organisations to empower market and street vendors who are women by establishing proper stalls. However, the government’s bureaucratic nature is the main obstacle in providing a suitable foundation for such projects.

The conditions of working women in Dhi Qar lack many elements of healthcare and social and economic welfare, forcing many women to work on the streets and pavements under the blazing sun during the peak of the summer heat, which locals call “the days of dates cooking” as the intense heat contributes to the ripening of the date harvest. However, all the ideas and programmes to support these women are, regrettably, yet to ripen.