Yazidis of Sinjar Cultivate their Lands but with No Prospect of Harvest

20 Jul 2023

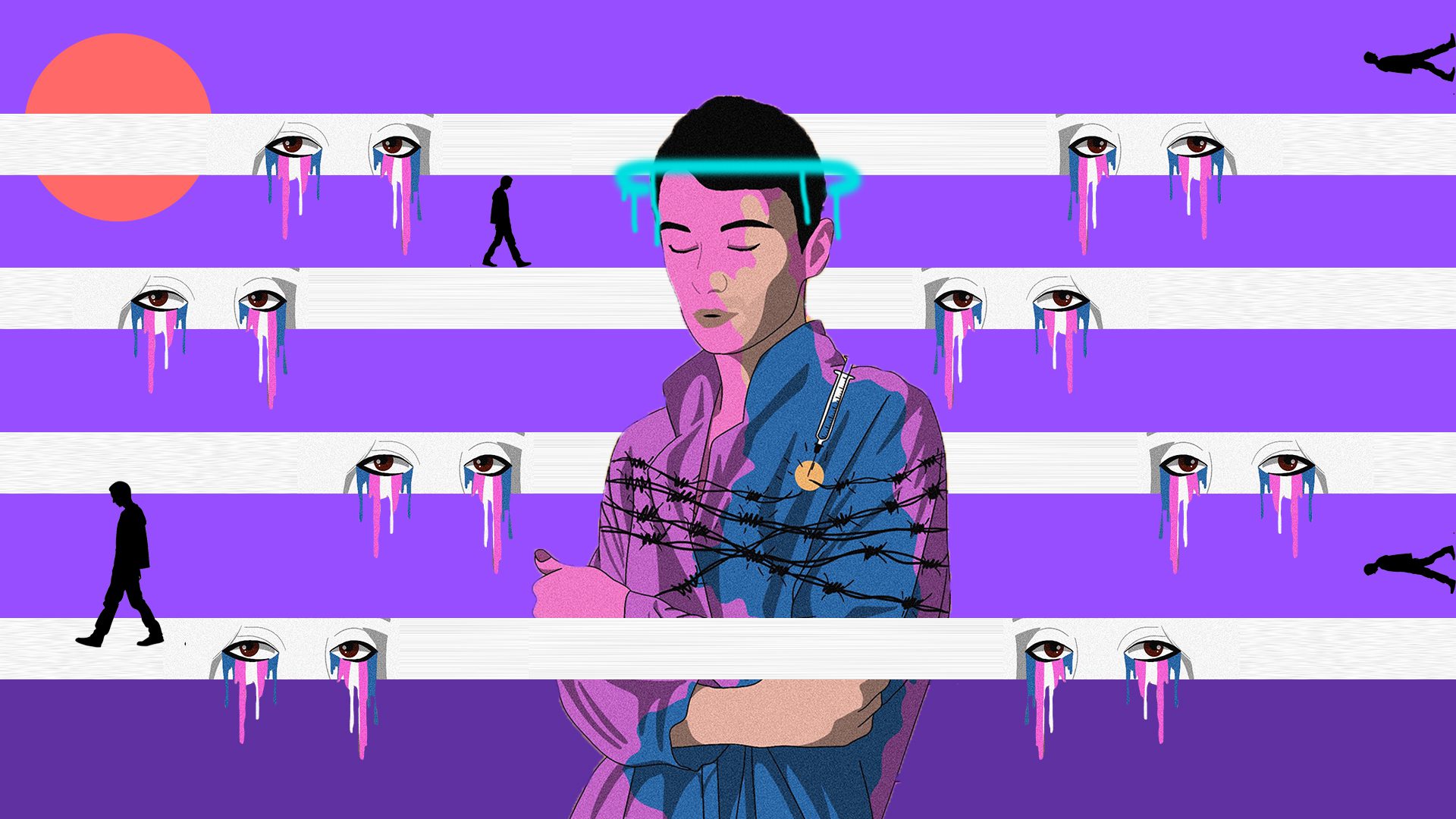

Khairu Eidou Elias keenly follows the mechanical reaper as it reaps the barley, despite knowing that the harvest will be meagre. He and Issa Bari attempt to revive lands destroyed by drought and war. The story of the transformation of Sinjar’s agriculture.

Issa Bari has cultivated wheat and barley on 1,500 dunums (one dunum equaling1000 square metres) of land without harvesting anything for three years. The land is in the village of Bari, north of the central Sinjar district in the Nineveh governorate. The terrain in this area has been suffering for decades from water scarcity and massive security scares, which have adversely affected agriculture.

“I lost more than seventy million dinars”, says Bari, a thirty-five-year-old Yazidi. In 2019, the barley crop in his land exceeded sixty tons, but he has been making a loss since 2020.

Bari could not return to his region due to the deterioration of agriculture and public services in Sinjar. Several members of his family remained in the Kabarto camp for displaced Yazidis in the Dohuk governorate in Kurdistan, and he came back to the village temporarily with part of his family to pursue his agricultural work. He hopes that the relevant authority will provide services and improve conditions so that they can return.

Bari left his village with his family of fourteen members after the Islamic State (ISIS) captured Sinjar in early August 2014. In 2017, he decided to return to the village. Still, his family could not stay with him due to the unstable security situation and lack of essential services, in addition to two of his sisters being enrolled in schools at an institute in Dohuk, which forced him to return to the Kabarto camp.

Only fifteen families out of fifty have now returned to Bari village, as the majority chose to stay in the Kurdistan Region and work in agriculture or other jobs due to Bari’s lack of basic living necessities.

A volatile area

The Yazidi-majority Sinjar district lies in the area of the Sinjar Mountain, which reaches a height of 1,400 metres and is more than 100 kilometres northwest of Mosul, situated along the Iraqi-Syrian border.

The Sinjar district has been a target of violence and its people have been harassed for decades. In 1975, the Ba’ath Party government carried out a campaign of enforced displacement against the Yazidis in Sinjar, evicting hundreds of families from at least 155 villages and relocating them to eleven residential complexes, some of which were built in the northern Sinjar Mountain district and others near Tal Uazir. This was because the Yazidis were accused of supporting the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, which opposed the political regime in Baghdad at the time.

Later, the families were forcibly evicted to other residential complexes, houses in Sinjar were bulldozed, and agricultural lands were burned to prevent their owners from returning. “Thousands of dunums of agricultural land belonging to the Qahtaniyah and northern Sinjar districts on the Iraqi-Syrian border were confiscated during Saddam Hussein’s regime, and the fate of these areas is still unknown today”, Sinjar district mayor, Fahd Hamid, told Jummar.

After the fall of the former regime in 2003, the displaced Yazidis tried returning to their villages, only to find them destroyed and uninhabitable so many of them chose to stay in the complexes.

The area remained in a dire state but then a still greater catastrophe struck on 3 August 2014, when Islamic State (ISIS) militants attacked Yazidi villages in Sinjar and the Nineveh Plains after the forces of the state and the Kurdish army fled. The extremist group killed no less than 1,200 Yazidis in that attack and kidnapped and enslaved more than six thousand Yazidi women, prompting the United Nations to consider it an act of genocide.

The area remained under the control of (ISIS) until November 2015, when it was recaptured by the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, including Yazidi fighters and the PKK, with air support from the US-led international coalition. The situation in Sinjar has been getting more complicated ever since.

The district was thereafter controlled by a Yazidi militia called the “Sinjar Protection Forces” (Al-Yibsha), loyal to the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK), an enemy of the Turkish government. It is also an Iranian ally and is classified as an international terrorist organisation. Al-Yibsha tightened its grip on Sinjar within the framework of agreements with pro-Iranian Iraqi armed groups that also have power in the district, including “Al-Nujabaa”, “Kataib Hezbollah”, and “Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq”.

On 9 October 2020, the government of former Prime Minister, Mustafa Al-Kazemi, agreed with the Kurdistan Regional Government to normalise the situation in Sinjar. The agreement included managing security in Sinjar by the federal government in coordination with Erbil, providing that Nineveh’s local government would manage services in the district. It also included removing members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and other armed groups from the district and handing them over to the national army and the federal police.

Two months after the agreement, military forces entered Sinjar and agreed with Al-Yibsha militants to surrender their positions in the city and withdraw to the outskirts. At the time, a spokesman for Al-Yibsha said that this force would be integrated into the Popular Mobilisation Forces under the name of the 80th Regiment, which indeed happened. However, the withdrawal of Al-Yibsha was a formal move, as it remained, along with the Workers’ Party, in control over Sinjar.

The army and Al-Yibsha are not friends. Clashes between the two broke out at the beginning of May 2022, displacing more than four thousand civilians from Sinjar towards Dohuk. The two parties exchanged finger-pointing regarding the reasons behind the clashes. The army accused Al-Yibsha of closing roads, erecting barricades, and preventing civilians from moving to the north. In contrast, Al-Yibsha accused the military of seeking to control and evict their forces from the city. The situation calmed down a few days later without any change in the security map.

Karim Shammou, a member of the local council in Sinjar, says that the presence of the Iraqi army can be considered “merely a face-saving move by the government”, as it has limited deployment and is prevented from entering some areas due to the objections of the Labour Party and Al-Yishba. At the present time, the Sinjar Agreement has not yet been implemented.

These old and new tensions in Sinjar led to a constraint on agriculture, just as on other activities and living conditions of the residents. Battles and unrest caused many problems that resulted in the deterioration of the water supply.

Total loss

Most Yazidis in Sinjar used to work in agriculture, which was the primary source of income before ISIS took control of their region, and they have good experience in various agricultural fields. However, the district has experienced severe drought during the past three years, significantly affecting the agricultural sector and water resources. Rain is not guaranteed in Sinjar, as it is located in an area with poor rainfall. Rainfall reached 242 millimetres in the 2020-2021 season, 232 millimetres in the 2021-2022 season, and 260 millimetres in the current season as of the end of April. These numbers are low on precipitation scales.

Yassin Jafar Mohsen, an agricultural expert, told Jummar that drought engulfed the region in the mid-1980s but was not as severe as now. Yazidis in Sinjar are seventy per cent dependent on agriculture, which has declined by fifty per cent over the past two years due to poor rainfall, according to Fahd Hamed, Sinjar district mayor. “The percentage of the Yazidi farmers’ loss has reached 100 per cent due to drought”, Hamid told Jummar.

Most Yazidi villages around Sinjar depended on springs, as there were over fifty to water crops. However, the springs have dried up successively, bringing their current number to less than ten. Wells were also destroyed and vandalised by ISIS and other criminals, according to Hamid, and only less than half of them remain where once they used to irrigate thousands of dunums that produced tons of various crops.

Around 400 artesian wells are within the borders of the Sinjar agriculture division, all of which belong to Yazidi farmers. Between 150 and 200 of them were destroyed due to ISIS militants’ attacks, military operations, vandalism and theft of the machines, water extraction equipment, power stations, and even the houses of the farmers themselves were taken over. This led to the wells ceasing to function.

“Orchards and agricultural fields were destroyed, and so were the farmers’ houses built on their farms. Power outages also affected the area due to the destruction and theft of electrical transformers”, said Sharaf Nayef Rashouka, Director of Sinjar Agriculture.

Humanitarian organisations have taken the initiative to help rehabilitate several wells and install solar panels to operate them, in addition to distributing greenhouses, chemical fertilisers, and pesticides to farmers currently in Sinjar. Eight wells are now operating using solar energy in Tal Banat and Al-Hatemiyeh, south of Sinjar, which were rehabilitated after being destroyed, and their power cut off due to ISIS militants occupying the area.

This situation caused unemployment among Yazidi farmers which reached eighty per cent. Sources of the Sinjar Farmers Union indicate that more than 570 Yazidi and Muslim farmers are registered with the union, but most of them are still displaced. According to the Director of Sinjar Agriculture, more than seventy-five per cent of the area’s population is still displaced due to the destruction of artesian wells, in addition to their farms and orchards.

War trenches

Many trenches and berms were constructed during the battles in the area by ISIS militants and security forces on agricultural land. “Some of these trenches are up to five metres wide”, said Ahmad Abdullah Massi, an official of the Farmers Union in Sinjar. Between the villages of Umm Al-Dhiban and Sino, east of Sinjar, farmers lost about 2,500 dunums in this area only due to berms and trenches.

Security authorities are not allowed to remove the berms and trenches for unknown reasons. However, Massi blames the displaced farmers. “The security situation in Sinjar is stable, and there are no excuses for them not to return”, he tells Jummar. He believes that the judicial and governmental authorities can generate procedures to manage any attacks or transgressions that farmers and villagers may face upon their return. He also accuses “biased media of trying to stir up trouble among the people of Sinjar”.

The total area of agricultural land in Sinjar is estimated at more than 720,000 dunums, of which 360,000 dunums are allocated for orchards, mainly containing fig trees, olives, and other fruits. Twenty years ago, each dunum of land cultivated with barley and wheat produced between 500 and 700 kilograms, according to Rashouka. Today, however, each dunum produces only 300 to 500 kilograms.

According to well-informed sources, the agricultural plan for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022 did not exceed the cultivation of 340,000 out of 360,000 dunums of land designated for wheat and barley, as the rest was not cultivated due to drought. Mohsen says that the harvest of the 2020-2021 season saw the trading of 15,000 tons of wheat and barley from the crops of Sinjar’s farmers, and 20,000 tons were traded in the 2021-2022 season, while the current season is expected to reach about 30,000 tons.

He points out that the agrarian structure in Sinjar is fragile due to drought and the former impact of ISIS militants’ control, which destroyed agriculture, wells, springs, streams, and agricultural machinery. He also stressed the need to follow modern agriculture methods, including the use of sprinklers in cultivating wheat and barley.

Specialists propose the construction of dams for water harvesting and rational investment of groundwater to preserve the cultivated areas and the social stability of the population. “Sinjar Mountain contains massive reserves of groundwater that could be obtained through drilling wells to depths exceeding 120 metres”, Ramadan Hamza, an expert in water policies, tells Jummar.

Hamza points to the large number of valleys that would facilitate the construction of hundreds of water-harvesting dams in the region. However, farmers cannot do this and revive agriculture independently without the state’s help.

“The agricultural situation requires great investment, providing agricultural supplies and machinery, and supporting farmers by providing seeds, pesticides, fertilisers, and fuel”, says Hamid, adding that “there is no real support for farmers from the state, and concerned authorities are negligent”.

One of the forms of government neglect of agriculture in Sinjar is the destruction of six thousand dunums of pine forests that were established in the seventies of the last century, as approximately two million trees of these forests were cut down and uprooted after 2005 to be used as firewood without governmental intervention to save them.

Better than nothing

The Yazidi farmer Khairu Eidou Elias (fifty years old) attentively and eagerly watches the mechanical reaper as it harvests the barley planted in his field in Tal Qasab, southern Sinjar. Although the size of his crop is much below the required level, Elias is satisfied after three seasons of drought. “It is better than nothing”, he tells Jummar.

The cost of crop cultivation increased due to drought, as the price of one ton of barley seeds reached 900,000 dinars, and one litre of fuel cost about 900 dinars. The rent for the mechanical reaper is 140,000 dinars per ten dunums, in addition to the cost of fertilisers, pesticides, and other supplies.

“Despite all these costs, we do not get enough government support,” Elias added.

*This article is supported by the Check Global Program – Meedan Foundation.

Read More

“His gaze was intrusive; it pierced my soul”: On the Struggles of Divorced Women in Navigating Courts and Governmental Institutions

“She Brought a Fatwa from Khamenei and Al-Azhar, But It Went Nowhere”: The Struggles of Trans People in the Iraqi Health Sector

“Everyone has a Right to the Kids Except their Mother”: On Women Fighting for the Custody of Their Children

Iraqi Prisoners Blackmailed to Pay To Obtain Release Papers After Completing Their Sentence

Issa Bari has cultivated wheat and barley on 1,500 dunums (one dunum equaling1000 square metres) of land without harvesting anything for three years. The land is in the village of Bari, north of the central Sinjar district in the Nineveh governorate. The terrain in this area has been suffering for decades from water scarcity and massive security scares, which have adversely affected agriculture.

“I lost more than seventy million dinars”, says Bari, a thirty-five-year-old Yazidi. In 2019, the barley crop in his land exceeded sixty tons, but he has been making a loss since 2020.

Bari could not return to his region due to the deterioration of agriculture and public services in Sinjar. Several members of his family remained in the Kabarto camp for displaced Yazidis in the Dohuk governorate in Kurdistan, and he came back to the village temporarily with part of his family to pursue his agricultural work. He hopes that the relevant authority will provide services and improve conditions so that they can return.

Bari left his village with his family of fourteen members after the Islamic State (ISIS) captured Sinjar in early August 2014. In 2017, he decided to return to the village. Still, his family could not stay with him due to the unstable security situation and lack of essential services, in addition to two of his sisters being enrolled in schools at an institute in Dohuk, which forced him to return to the Kabarto camp.

Only fifteen families out of fifty have now returned to Bari village, as the majority chose to stay in the Kurdistan Region and work in agriculture or other jobs due to Bari’s lack of basic living necessities.

A volatile area

The Yazidi-majority Sinjar district lies in the area of the Sinjar Mountain, which reaches a height of 1,400 metres and is more than 100 kilometres northwest of Mosul, situated along the Iraqi-Syrian border.

The Sinjar district has been a target of violence and its people have been harassed for decades. In 1975, the Ba’ath Party government carried out a campaign of enforced displacement against the Yazidis in Sinjar, evicting hundreds of families from at least 155 villages and relocating them to eleven residential complexes, some of which were built in the northern Sinjar Mountain district and others near Tal Uazir. This was because the Yazidis were accused of supporting the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, which opposed the political regime in Baghdad at the time.

Later, the families were forcibly evicted to other residential complexes, houses in Sinjar were bulldozed, and agricultural lands were burned to prevent their owners from returning. “Thousands of dunums of agricultural land belonging to the Qahtaniyah and northern Sinjar districts on the Iraqi-Syrian border were confiscated during Saddam Hussein’s regime, and the fate of these areas is still unknown today”, Sinjar district mayor, Fahd Hamid, told Jummar.

After the fall of the former regime in 2003, the displaced Yazidis tried returning to their villages, only to find them destroyed and uninhabitable so many of them chose to stay in the complexes.

The area remained in a dire state but then a still greater catastrophe struck on 3 August 2014, when Islamic State (ISIS) militants attacked Yazidi villages in Sinjar and the Nineveh Plains after the forces of the state and the Kurdish army fled. The extremist group killed no less than 1,200 Yazidis in that attack and kidnapped and enslaved more than six thousand Yazidi women, prompting the United Nations to consider it an act of genocide.

The area remained under the control of (ISIS) until November 2015, when it was recaptured by the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, including Yazidi fighters and the PKK, with air support from the US-led international coalition. The situation in Sinjar has been getting more complicated ever since.

The district was thereafter controlled by a Yazidi militia called the “Sinjar Protection Forces” (Al-Yibsha), loyal to the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK), an enemy of the Turkish government. It is also an Iranian ally and is classified as an international terrorist organisation. Al-Yibsha tightened its grip on Sinjar within the framework of agreements with pro-Iranian Iraqi armed groups that also have power in the district, including “Al-Nujabaa”, “Kataib Hezbollah”, and “Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq”.

On 9 October 2020, the government of former Prime Minister, Mustafa Al-Kazemi, agreed with the Kurdistan Regional Government to normalise the situation in Sinjar. The agreement included managing security in Sinjar by the federal government in coordination with Erbil, providing that Nineveh’s local government would manage services in the district. It also included removing members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and other armed groups from the district and handing them over to the national army and the federal police.

Two months after the agreement, military forces entered Sinjar and agreed with Al-Yibsha militants to surrender their positions in the city and withdraw to the outskirts. At the time, a spokesman for Al-Yibsha said that this force would be integrated into the Popular Mobilisation Forces under the name of the 80th Regiment, which indeed happened. However, the withdrawal of Al-Yibsha was a formal move, as it remained, along with the Workers’ Party, in control over Sinjar.

The army and Al-Yibsha are not friends. Clashes between the two broke out at the beginning of May 2022, displacing more than four thousand civilians from Sinjar towards Dohuk. The two parties exchanged finger-pointing regarding the reasons behind the clashes. The army accused Al-Yibsha of closing roads, erecting barricades, and preventing civilians from moving to the north. In contrast, Al-Yibsha accused the military of seeking to control and evict their forces from the city. The situation calmed down a few days later without any change in the security map.

Karim Shammou, a member of the local council in Sinjar, says that the presence of the Iraqi army can be considered “merely a face-saving move by the government”, as it has limited deployment and is prevented from entering some areas due to the objections of the Labour Party and Al-Yishba. At the present time, the Sinjar Agreement has not yet been implemented.

These old and new tensions in Sinjar led to a constraint on agriculture, just as on other activities and living conditions of the residents. Battles and unrest caused many problems that resulted in the deterioration of the water supply.

Total loss

Most Yazidis in Sinjar used to work in agriculture, which was the primary source of income before ISIS took control of their region, and they have good experience in various agricultural fields. However, the district has experienced severe drought during the past three years, significantly affecting the agricultural sector and water resources. Rain is not guaranteed in Sinjar, as it is located in an area with poor rainfall. Rainfall reached 242 millimetres in the 2020-2021 season, 232 millimetres in the 2021-2022 season, and 260 millimetres in the current season as of the end of April. These numbers are low on precipitation scales.

Yassin Jafar Mohsen, an agricultural expert, told Jummar that drought engulfed the region in the mid-1980s but was not as severe as now. Yazidis in Sinjar are seventy per cent dependent on agriculture, which has declined by fifty per cent over the past two years due to poor rainfall, according to Fahd Hamed, Sinjar district mayor. “The percentage of the Yazidi farmers’ loss has reached 100 per cent due to drought”, Hamid told Jummar.

Most Yazidi villages around Sinjar depended on springs, as there were over fifty to water crops. However, the springs have dried up successively, bringing their current number to less than ten. Wells were also destroyed and vandalised by ISIS and other criminals, according to Hamid, and only less than half of them remain where once they used to irrigate thousands of dunums that produced tons of various crops.

Around 400 artesian wells are within the borders of the Sinjar agriculture division, all of which belong to Yazidi farmers. Between 150 and 200 of them were destroyed due to ISIS militants’ attacks, military operations, vandalism and theft of the machines, water extraction equipment, power stations, and even the houses of the farmers themselves were taken over. This led to the wells ceasing to function.

“Orchards and agricultural fields were destroyed, and so were the farmers’ houses built on their farms. Power outages also affected the area due to the destruction and theft of electrical transformers”, said Sharaf Nayef Rashouka, Director of Sinjar Agriculture.

Humanitarian organisations have taken the initiative to help rehabilitate several wells and install solar panels to operate them, in addition to distributing greenhouses, chemical fertilisers, and pesticides to farmers currently in Sinjar. Eight wells are now operating using solar energy in Tal Banat and Al-Hatemiyeh, south of Sinjar, which were rehabilitated after being destroyed, and their power cut off due to ISIS militants occupying the area.

This situation caused unemployment among Yazidi farmers which reached eighty per cent. Sources of the Sinjar Farmers Union indicate that more than 570 Yazidi and Muslim farmers are registered with the union, but most of them are still displaced. According to the Director of Sinjar Agriculture, more than seventy-five per cent of the area’s population is still displaced due to the destruction of artesian wells, in addition to their farms and orchards.

War trenches

Many trenches and berms were constructed during the battles in the area by ISIS militants and security forces on agricultural land. “Some of these trenches are up to five metres wide”, said Ahmad Abdullah Massi, an official of the Farmers Union in Sinjar. Between the villages of Umm Al-Dhiban and Sino, east of Sinjar, farmers lost about 2,500 dunums in this area only due to berms and trenches.

Security authorities are not allowed to remove the berms and trenches for unknown reasons. However, Massi blames the displaced farmers. “The security situation in Sinjar is stable, and there are no excuses for them not to return”, he tells Jummar. He believes that the judicial and governmental authorities can generate procedures to manage any attacks or transgressions that farmers and villagers may face upon their return. He also accuses “biased media of trying to stir up trouble among the people of Sinjar”.

The total area of agricultural land in Sinjar is estimated at more than 720,000 dunums, of which 360,000 dunums are allocated for orchards, mainly containing fig trees, olives, and other fruits. Twenty years ago, each dunum of land cultivated with barley and wheat produced between 500 and 700 kilograms, according to Rashouka. Today, however, each dunum produces only 300 to 500 kilograms.

According to well-informed sources, the agricultural plan for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022 did not exceed the cultivation of 340,000 out of 360,000 dunums of land designated for wheat and barley, as the rest was not cultivated due to drought. Mohsen says that the harvest of the 2020-2021 season saw the trading of 15,000 tons of wheat and barley from the crops of Sinjar’s farmers, and 20,000 tons were traded in the 2021-2022 season, while the current season is expected to reach about 30,000 tons.

He points out that the agrarian structure in Sinjar is fragile due to drought and the former impact of ISIS militants’ control, which destroyed agriculture, wells, springs, streams, and agricultural machinery. He also stressed the need to follow modern agriculture methods, including the use of sprinklers in cultivating wheat and barley.

Specialists propose the construction of dams for water harvesting and rational investment of groundwater to preserve the cultivated areas and the social stability of the population. “Sinjar Mountain contains massive reserves of groundwater that could be obtained through drilling wells to depths exceeding 120 metres”, Ramadan Hamza, an expert in water policies, tells Jummar.

Hamza points to the large number of valleys that would facilitate the construction of hundreds of water-harvesting dams in the region. However, farmers cannot do this and revive agriculture independently without the state’s help.

“The agricultural situation requires great investment, providing agricultural supplies and machinery, and supporting farmers by providing seeds, pesticides, fertilisers, and fuel”, says Hamid, adding that “there is no real support for farmers from the state, and concerned authorities are negligent”.

One of the forms of government neglect of agriculture in Sinjar is the destruction of six thousand dunums of pine forests that were established in the seventies of the last century, as approximately two million trees of these forests were cut down and uprooted after 2005 to be used as firewood without governmental intervention to save them.

Better than nothing

The Yazidi farmer Khairu Eidou Elias (fifty years old) attentively and eagerly watches the mechanical reaper as it harvests the barley planted in his field in Tal Qasab, southern Sinjar. Although the size of his crop is much below the required level, Elias is satisfied after three seasons of drought. “It is better than nothing”, he tells Jummar.

The cost of crop cultivation increased due to drought, as the price of one ton of barley seeds reached 900,000 dinars, and one litre of fuel cost about 900 dinars. The rent for the mechanical reaper is 140,000 dinars per ten dunums, in addition to the cost of fertilisers, pesticides, and other supplies.

“Despite all these costs, we do not get enough government support,” Elias added.

*This article is supported by the Check Global Program – Meedan Foundation.