Water Means Everything.. The Migration of People and Animals of the Marshes from Paradise to Cities

01 Oct 2022

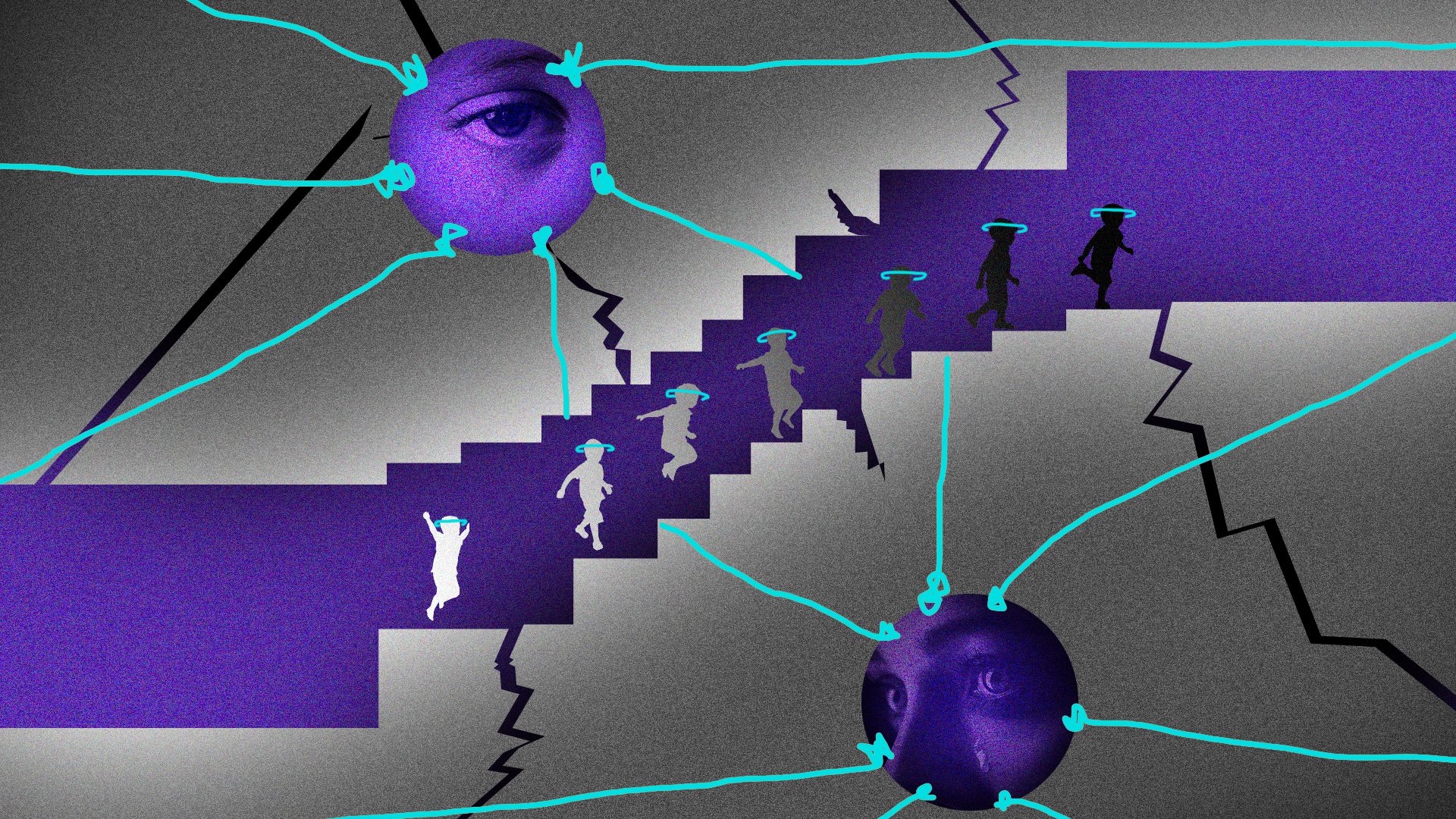

Hamza Salman and Abu Ali watched the water disappear around them. They had to save what could be saved in order to continue living. As one of them embarks on a migration journey, the second hopes for a miraculous solution.

Hamza Salman had to leave his village Histcha in the district of Al-Jbayish (90 km south of Thi Qar governorate) to go to Babil governorate after the land around him dried up. About 40 families in his neighborhood also left their homes. When I met Salman, a young man in his late twenties covered by marks left by the scorching sun, he was preparing his belongings, himself and his animals to bid farewell to Histcha, the place where he was born and where his ancestors had lived for decades before him.

Salman struggled to survive in his village, where houses are built out of mud, surrounded by water and with reeds on the river banks. Buffalo float on the surface of its waters. Neither Salman nor his animals are able to cope with the drought that has hit all that is around them.

When the summer of 2022 arrived, Salman saw the water levels decrease day by day. He was forced to buy sterilized water to save his family and his buffalo from drying out. He could not stand this situation: “Nothing can go on without water, reeds, animals and everything that is related. We need water.”

Salman’s is not an unusual case. Al Tawasul Wa Al-Ekha Organisation– a civil institution in Dhi Qar that is concerned with the environment – recorded the migration of about 530 families from different districts in Dhi Qar governorate during the summer months of this year due to water scarcity, high salinity rates and increasing rates of unemployment. “These people have moved on to the governorates of Karbala and Maysan. We are facing wide risks,” according to Ali Al-Nashi, the head of the organization.

A threatened Garden of Eden

The marshes, known as the Garden of Eden, are plains of water that extend over 20 thousand km2 across southern Iraq and are linked to three governorates: Maysan, Dhi Qar and Basra. The Huwaizah and Western Hammar Marshes make up the natural part of what is known as the Ahwar of Southern Iraq and are one of the most important centers of ecological and biological balance in the world, and for this reason have named in the World Heritage List by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The organization described the water plains as a “unique region, as the largest region in the world with inland delta systems, in a hot and arid environment.”

However, the heat of the atmosphere, the arid lands surrounding it, and the cuts to water flow and supply by Iran and Turkey, have seen the “Bata’eh[1]” dry up and become devasted.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) classifies the marshes as “one of the poorest areas in Iraq and one of the areas most affected by climate change”. FAO notes that the lack of water has had catastrophic effects on the livelihoods of more than 6,000 rural families, as they have lost their buffalo, which is their one unique living asset.

Hassan al-Asadi, a member of parliament for the Chabayish district, estimates that “more than 85% of the water plains have completely dried up.”

Threatened Economy

In Chabayish, Abu Ali is standing in front of his village which is turning to ruins with his hands are folded to his chest. He used to leave his house to see water surrounding the village. Now, he brings water now to his family and buffaloes on his motorbike, and buys fodder from local markets.

The man is waiting for some miracle to happen.“Perhaps the sky will be kind (with rain) one day, or the water will return.”

The livelihood of Hamza Salman, Abu Ali and the majority of the population depends on the natural recovery in the marshes, which would mean the recovery of reeds and plants on the banks of the water, thus providing food and a healthy environment for buffalo and fish.The inhabitants of the marshes are divided into two parts: the first whose economy depends on raising buffaloes, and the second on fishing.

Breeding or hunting many animals has become almost impossible. Buffalo, for example, need a half of a meter submersion rate to exercise within the water, and water which is much less salty than is the case today. In the marshes, where the water is still flowing, the salinity has increased from 6 thousand parts to 20 thousand parts per million.

According to available statistics, 2.7% of the 27 thousand buffalo have died due to lack of water and increased salinity. ENumbers indicate that on average each family in the marshes owns about 10 buffaloes. This means that, in addition to the death of 2.7%, approximately 5,300 buffaloes have left the area in the last few months.

As for those who have remained in the marshes hoping for better conditions, they have had to make various sacrifices. Before the drought, the price of one buffalo was estimated at around 3 and a half million Iraqi dinars, but its livelihood, which became threatened, and feeding it, which became impossible, has seen its value drop to approximately two and a quarter million Iraqi dinars. Buffalo keepers have lost 20% of their animals, either through selling them because they were no longer able to feed it or save it, or by sacrificing some to save the rest of the herd.

Fish farmers’ livelihood and their life in the marshes is also under real and greater threat. There are huge numbers of dead fish floating on the face of the remaining water, or running in the streams of stagnant rivers.Quantities of exported fish have decreased by 90%. Instead of the usual 80 tons, only 10 tons are exported to neighboring local markets, according to Ayad al-Asadi, an environmental activist who has been closely monitoring the transformation of the marshes.The death of fish has affected their prices, as the price of a kilo has doubled, sold for 6,000 IQD instead of 3,000 IQD.

In the midst of this, an incident where nearly 750 out of 1000 wooden boats became stuck in barren lands that were lightly cruising the water plains and their captains singing in melodious voices. Raad al-Asadi, head of the Al-Chibayish Eco-Tourism Organization, which monitors water plains, said, “The streams of the water plains used to receive 6 new boats per week,”. But the makers of this fishing and transport tools are no longer working now.

Dark Future

Despite the drought and worsening migration from the marshes, Mahdi al-Hamdani, Minister of Water Resources, says that “the situation today is better than tomorrow.” Al-Hamdani, and ministers who preceded him, have conducted countless rounds of consultations with neighbouring countries, Turkey and Iran, to increase water supply to Iraq. His efforts have been unsuccessful.

On his visit to Basra Governorate in August 2022, Al-Hamdani referenced what he saw as the worst scenario that could hit Iraq: “Everyone should be aware of the reality of the great risks to water resources in light of recorded temperatures exceeding 50 Celsius degrees. These are dangerous indicators for the next season.” According to the Ministry of Water Resources, Iraq has been through four seasons of water scarcity, and may enter its fifth season. It has been forced to rely on groundwater and enter an emergency phase. In the marshes, the inhabitants have already entered the phase of emergency, and are having to find individual solutions. Many of Salman’s relatives immigrated to the province of Babel, where there is still water that helps the buffalo to live. He will be accompanied by 15 buffalos and 4 cows, leaving Histcha for to its fate, which will be determined by the rains to come in the winter season.

Read More

“His gaze was intrusive; it pierced my soul”: On the Struggles of Divorced Women in Navigating Courts and Governmental Institutions

“She Brought a Fatwa from Khamenei and Al-Azhar, But It Went Nowhere”: The Struggles of Trans People in the Iraqi Health Sector

“Everyone has a Right to the Kids Except their Mother”: On Women Fighting for the Custody of Their Children

Iraqi Prisoners Blackmailed to Pay To Obtain Release Papers After Completing Their Sentence

Hamza Salman had to leave his village Histcha in the district of Al-Jbayish (90 km south of Thi Qar governorate) to go to Babil governorate after the land around him dried up. About 40 families in his neighborhood also left their homes. When I met Salman, a young man in his late twenties covered by marks left by the scorching sun, he was preparing his belongings, himself and his animals to bid farewell to Histcha, the place where he was born and where his ancestors had lived for decades before him.

Salman struggled to survive in his village, where houses are built out of mud, surrounded by water and with reeds on the river banks. Buffalo float on the surface of its waters. Neither Salman nor his animals are able to cope with the drought that has hit all that is around them.

When the summer of 2022 arrived, Salman saw the water levels decrease day by day. He was forced to buy sterilized water to save his family and his buffalo from drying out. He could not stand this situation: “Nothing can go on without water, reeds, animals and everything that is related. We need water.”

Salman’s is not an unusual case. Al Tawasul Wa Al-Ekha Organisation– a civil institution in Dhi Qar that is concerned with the environment – recorded the migration of about 530 families from different districts in Dhi Qar governorate during the summer months of this year due to water scarcity, high salinity rates and increasing rates of unemployment. “These people have moved on to the governorates of Karbala and Maysan. We are facing wide risks,” according to Ali Al-Nashi, the head of the organization.

A threatened Garden of Eden

The marshes, known as the Garden of Eden, are plains of water that extend over 20 thousand km2 across southern Iraq and are linked to three governorates: Maysan, Dhi Qar and Basra. The Huwaizah and Western Hammar Marshes make up the natural part of what is known as the Ahwar of Southern Iraq and are one of the most important centers of ecological and biological balance in the world, and for this reason have named in the World Heritage List by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The organization described the water plains as a “unique region, as the largest region in the world with inland delta systems, in a hot and arid environment.”

However, the heat of the atmosphere, the arid lands surrounding it, and the cuts to water flow and supply by Iran and Turkey, have seen the “Bata’eh[1]” dry up and become devasted.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) classifies the marshes as “one of the poorest areas in Iraq and one of the areas most affected by climate change”. FAO notes that the lack of water has had catastrophic effects on the livelihoods of more than 6,000 rural families, as they have lost their buffalo, which is their one unique living asset.

Hassan al-Asadi, a member of parliament for the Chabayish district, estimates that “more than 85% of the water plains have completely dried up.”

Threatened Economy

In Chabayish, Abu Ali is standing in front of his village which is turning to ruins with his hands are folded to his chest. He used to leave his house to see water surrounding the village. Now, he brings water now to his family and buffaloes on his motorbike, and buys fodder from local markets.

The man is waiting for some miracle to happen.“Perhaps the sky will be kind (with rain) one day, or the water will return.”

The livelihood of Hamza Salman, Abu Ali and the majority of the population depends on the natural recovery in the marshes, which would mean the recovery of reeds and plants on the banks of the water, thus providing food and a healthy environment for buffalo and fish.The inhabitants of the marshes are divided into two parts: the first whose economy depends on raising buffaloes, and the second on fishing.

Breeding or hunting many animals has become almost impossible. Buffalo, for example, need a half of a meter submersion rate to exercise within the water, and water which is much less salty than is the case today. In the marshes, where the water is still flowing, the salinity has increased from 6 thousand parts to 20 thousand parts per million.

According to available statistics, 2.7% of the 27 thousand buffalo have died due to lack of water and increased salinity. ENumbers indicate that on average each family in the marshes owns about 10 buffaloes. This means that, in addition to the death of 2.7%, approximately 5,300 buffaloes have left the area in the last few months.

As for those who have remained in the marshes hoping for better conditions, they have had to make various sacrifices. Before the drought, the price of one buffalo was estimated at around 3 and a half million Iraqi dinars, but its livelihood, which became threatened, and feeding it, which became impossible, has seen its value drop to approximately two and a quarter million Iraqi dinars. Buffalo keepers have lost 20% of their animals, either through selling them because they were no longer able to feed it or save it, or by sacrificing some to save the rest of the herd.

Fish farmers’ livelihood and their life in the marshes is also under real and greater threat. There are huge numbers of dead fish floating on the face of the remaining water, or running in the streams of stagnant rivers.Quantities of exported fish have decreased by 90%. Instead of the usual 80 tons, only 10 tons are exported to neighboring local markets, according to Ayad al-Asadi, an environmental activist who has been closely monitoring the transformation of the marshes.The death of fish has affected their prices, as the price of a kilo has doubled, sold for 6,000 IQD instead of 3,000 IQD.

In the midst of this, an incident where nearly 750 out of 1000 wooden boats became stuck in barren lands that were lightly cruising the water plains and their captains singing in melodious voices. Raad al-Asadi, head of the Al-Chibayish Eco-Tourism Organization, which monitors water plains, said, “The streams of the water plains used to receive 6 new boats per week,”. But the makers of this fishing and transport tools are no longer working now.

Dark Future

Despite the drought and worsening migration from the marshes, Mahdi al-Hamdani, Minister of Water Resources, says that “the situation today is better than tomorrow.” Al-Hamdani, and ministers who preceded him, have conducted countless rounds of consultations with neighbouring countries, Turkey and Iran, to increase water supply to Iraq. His efforts have been unsuccessful.

On his visit to Basra Governorate in August 2022, Al-Hamdani referenced what he saw as the worst scenario that could hit Iraq: “Everyone should be aware of the reality of the great risks to water resources in light of recorded temperatures exceeding 50 Celsius degrees. These are dangerous indicators for the next season.” According to the Ministry of Water Resources, Iraq has been through four seasons of water scarcity, and may enter its fifth season. It has been forced to rely on groundwater and enter an emergency phase. In the marshes, the inhabitants have already entered the phase of emergency, and are having to find individual solutions. Many of Salman’s relatives immigrated to the province of Babel, where there is still water that helps the buffalo to live. He will be accompanied by 15 buffalos and 4 cows, leaving Histcha for to its fate, which will be determined by the rains to come in the winter season.