The Tishreen Museum: A project to document an uprising ends up destroyed

03 Oct 2022

Mustafa Al-Kadhemi’s brother and advisor argued for a lawsuit that prevented the Turkish restaurant from being transferred into a Tishreen Museum. The judiciary denies this, and the rest of the institutions reply: “We don’t know.”

An abandoned building with soot rising on its walls. Its gate is closed and, from the bare window openings on its three sides, people passing by can see soldiers sitting behind random barricades.

This is the Turkish Restaurant in the heart of Baghdad. Its front overlooks Tahrir Square and behind it is the fortified Green Zone. It stands high on the neck of the Jumhuriya Bridge from the side of Rusafa. The place is gloomy and evokes a feeling of fear when approaching it at night. One can no longer hear the noise and enthusiastic songs that came from it. Nor see the green laser lights that used to descend as sharp columns from its windows onto the protesters and the riot police.

Protest Center

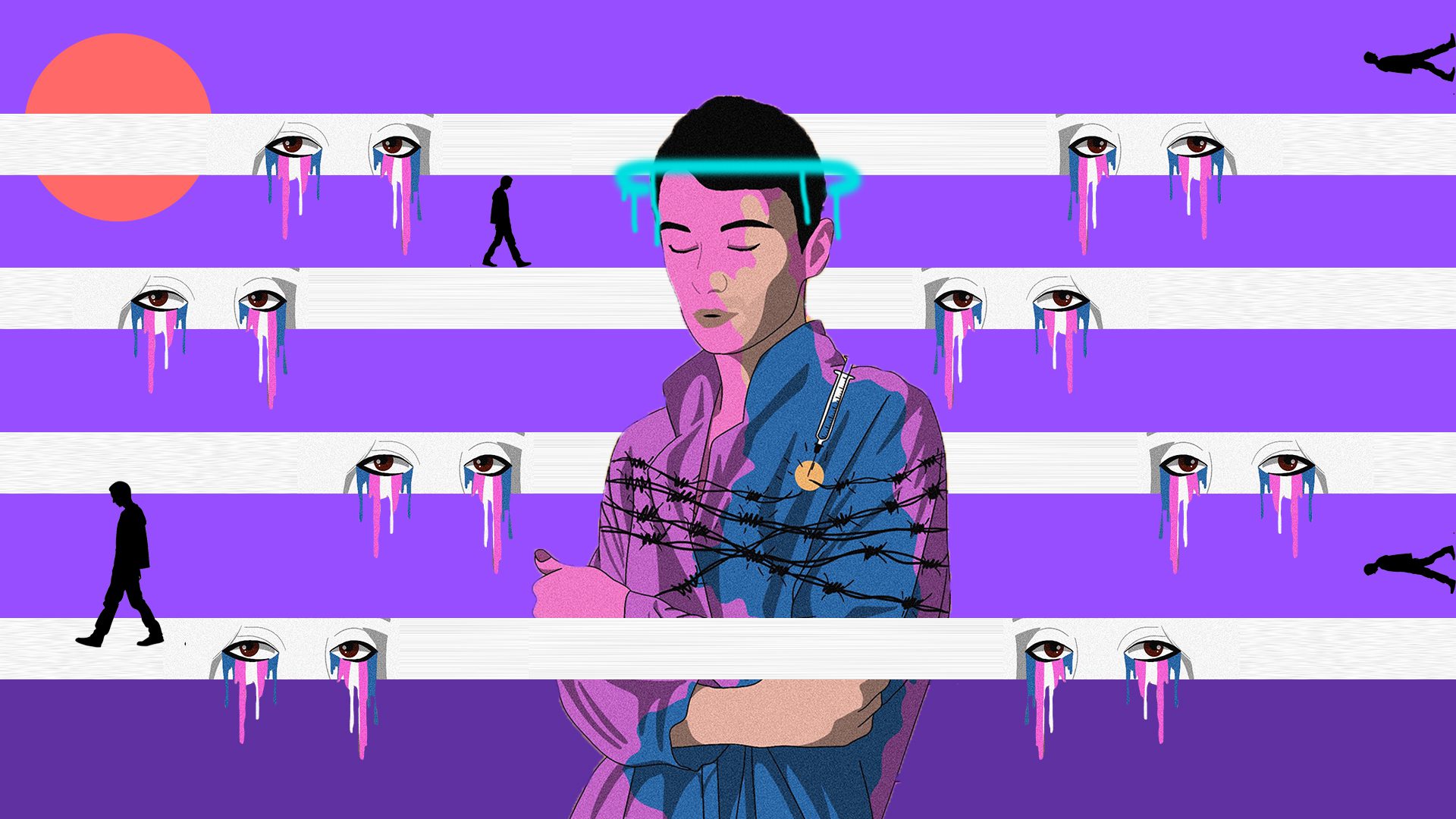

For months, starting in October 2019, and continuing until the middle of the following year, the building known as the Turkish Restaurant was a key symbol of the popular protests that swept the cities of central and southern Iraq. A large Iraqi flag and slogans hung from it which expressed the aspirations and dreams of a new post-2003 generation who see no future as a result of corruption in state institutions and conflicts brought about by external influence in Iraqi affairs.

The 14-storey building was built in 1983. Iraqis named it after the Turkish restaurant that occupied its top floor. It had a panoramic design, and its walls were filled with pictures of rejected politicians, whose faces are marked with an X. However, the high-rise building also had a strategic dimension, in addition to the symbolism that these slogans and images provided. Protesters used it as a shelter and as a watchtower to monitor the movement of security forces as they progressed towards Tahrir Square.

When they later descended from “Uhud Mountain[1],” to avoid the security forces, they could not agree on the end. More than 800 demonstrators were killed and over 25,000 injured, in addition to hundreds of emigrants, out of fear of persecution. These angry youths achieved little of their goals other than the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi and his government, and the amendment of the election law. When the head of the intelligence service, Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, took over the formation of an interim government whose main task was to hold early elections, he began making promises to them as they were leaving the squares. In addition to his pledge to prosecute and hold accountable the killers of protesters and activists, whom the authorities referred to as third parties without specifying their identities, Al-Kadhemi dictated on November 12 that the Turkish restaurant would be transformed into a Tishreen Museum. “The October demonstrations are a lesson for us all. Your rights will not be lost,” he said, addressing the angry protesters. Some political parties considered him to be siding with the protesters at that time.

Al-Kadhemi’s office soon erected a sign on the building that read Tishreen Museum with the phrase “With the support and patronage of Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhemi.” According to the sign, the Prime Minister’s Office was responsible for supervising the museum’s work, and the name of Consultant Architect Saman Kamal” was also placed on the sign. Saman Asaad Kamal is known for his friendship and closeness to the Iraqi artist Ismail Fattah al-Turk. Their relationship saw work on one of Baghdad’s most important landmarks, the Martyr’s Monument.

In contrast to Kamal’s eagerness to talk about the various stages of completion with the Martyr’s Monument, his approach to the Tishreen Museum was devoid of enthusiasm. “The project is on hold,” he said. “I designed it, but it was not implemented for reasons that have nothing to do with me,” he added.

Like Kamal, several government institutions claim to not know about the museum’s fate, as the discussion about it was confined to the Prime Minister’s Office. Ahmed Al-Aliawi, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Culture, confirmed that they did not receive any instructions to turn the Turkish restaurant into a museum. He said that the Prime Minister “at the time assigned a committee to study this issue. A staff of engineers and architects was identified.” The Ministry of Culture had an idea to turn the building into a public art museum dedicating one of its floors to a memorial of the Tishreen demonstrations, but this was not achieved, according to Al-Aliawi. The Council of Ministers and its president, Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, are the sponsors of the museum project. As such, the Ministry of Culture does not have any details about it and what happened to it. The Municipality of Baghdad said that the project had not yet been approved by the Council of Ministers, and its spokesperson did not provide any details.

On August 23, 2021, Sabah Mashtat, Mustafa al-Kadhemi’s brother and advisor to some Iraqi media outlets, said that a legal problem had impeded the conversion of the Turkish restaurant into a museum. He stated that lawsuit had been claiming to be from the owner of the building with a previous investment license from the Baghdad Municipality. Mashtat said, “It is not possible to proceed with converting it into a museum without resolving the ownership problem.” However, an official source in the Supreme Judicial Council denied this was true in an interview with Jummar. Without using the diplomatic tone he is known for in the judiciary, he said, “The place is not governmental. There is no investment, there is no museum or anything like that. It is abandoned and neglected, and the harsh weather has destroyed the banner which was put in by the Prime Minister’s Office.”

Center of Power

In 2011, when Iraq also witnessed large-scale protests, the high-rise concrete building which had been abandoned since the occupation of Baghdad in April 2003, became the centre of operations to quash protests in Tahrir Square. Politicians and security commanders stood on the building’s balconies carrying communication devices to convey the situation to the centres of power. Surveillance cameras were installed at its corners, which facilitated the suppression and dispersal of angry gatherings.

For this reason, many of the new political groups that have emerged from the more recent protests believe that these parties, which have been deal with using a tight security grip, would never accept the building as a museum. The National Home Party “Al-Bait A-Wattani” is one of these movements. “The demands of the political and public uprising have not been fulfilled. It is too early to talk about the establishment of a museum that commemorates Tishreen because Tishreen has not ended,” Yasser Adnan, Deputy Secretary-General of the National Home Party, said.

Adnan believes that the museum represents “the government’s intention to convey an image that suggests the end of the October protests, that they have now become a thing of the past.” The problem is not, as he sees Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, “who was not the candidate of the protesters. To say that his government is the product of the demonstrations is very false.”

“There are influential political parties who will try to distort history because it exposes them and reminds them of the ugliness and criminality of the political authority that ruled Iraq at the time. These parties are still from within this authority and will oppose such projects (i.e. the Tishreen Museum) and try to falsify and distort the history of the uprising.”

“The lack of interest by successive and current governments in the cultural aspects of the Iraqi heritage and the lack of buildings, institutions, edifices and museums befitting Iraq’s history, which is one of the oldest civilizations in the universe,” confirms the fate of the establishment of a museum for the October protests.

For him, “implementing the demands of the protests and working on legislative and legal reforms and all governmental and societal sectors” takes precedence over the establishment of the museum. “Tishreen does not need it to be immortalized. Many historians, writers and authors wrote about it. The Iraqi memory is not fragmented enough to forget what happened.” And if the building of the Turkish Restaurant must be converted into a museum, “the real protesters, protest movements, institutions and emerging parties emanating from the demonstrations must be involved in laying the foundations of the museum so as not to interpret or distort the course of the October protest, its history and goals.”

Meanwhile, MP Sajjad Salem said that “the period after (the October protests) should be a period of political struggle in order to achieve the values of the revolution.” The head of the Artists Syndicate, Jabbar Judy, presented a proposal for the building of the Turkish Restaurant. If the building were to be restored to its original condition, with a parking lot and a restaurant on the last floor, it will become a Baghdad landmark. Judy does not like the current museum plan. “What will the government put inside the museum to commemorate the October uprising? The blood of the martyrs or the gas canisters? What will they put in it?” he wondered. Judy said, “The October revolution was immortalized by social media and visual media, which has more than what the museum might include. We do not see any point in it.”

Absorbing the Anger

Sajjad Salem won a seat in Parliament during the elections of October 2021. Like most of his voters, Salem participated in the Tishreen demonstrations in Wasit Governorate, and became an independent representative of his governorate. He does not see the government being serious about turning the Turkish restaurant into a museum that will commemorate the protests. He accuses it of “launching the idea merely to absorb public anger following demands to perpetuate the revolution.” Salem describes the idea of the museum as good, in order “to witness a great mass uprising and remind future generations of its values, wounds, suffering, oppression and all of the tragic events that accompanied it.”

The Extension “Imtidad” movement also has a similar view. This political movement emerged from the protests and won 9 parliamentary seats in the last elections. Its spokesperson Rasoul al-Saray told Jummar that the movement was briefed on the project to convert the Turkish restaurant into a museum documenting the October protests. Al-Saray also sees the project as “a way to absorb the anger of the demonstrators at the time,” adding, “The government has not taken any step to implement it so far.’ He still supports his idea and considers it a “seed of freedom for future generations to learn (through the supposed museum) about the experiences of disassociation from the consequences of intellectual, ideological and factional misinformation.”

The building, he says, “forms, along with Tahrir Square, a spiritual shrine for citizens with all their ideas and ideologies. In it there is a serenity that captures the souls of passers-by, bearing memories of the birth of a homeland for which free people sacrificed hundreds of human sacrifices in order to flourish and grow up free.” However, he is apprehensive and believes that the idea of the museum could threaten the fate of any protests that might take place in the near future.

“Converting the Turkish restaurant into a museum will give future governments a guaranteed secure gate to the Green Zone. The government will have its hand in it plus a key to its treasury, and this will prevent it being used as a shelter or place to gather. It will also secure the main entrance to the government zone, and thus it will be a legalized and captured symbol for all subsequent government. “

The tone of the consultant engineer Saman Asaad Kemal Chi was curt when asked whether the Turkish restaurant building will remain deserted, “There is nothing new in the (museum) project…the project is on hold.”

Read More

“She Brought a Fatwa from Khamenei and Al-Azhar, But It Went Nowhere”: The Struggles of Trans People in the Iraqi Health Sector

“Everyone has a Right to the Kids Except their Mother”: On Women Fighting for the Custody of Their Children

Iraqi Prisoners Blackmailed to Pay To Obtain Release Papers After Completing Their Sentence

“We Have to Make a Living Somehow”: Women Working Hard under the Heat of Dhi Qar

An abandoned building with soot rising on its walls. Its gate is closed and, from the bare window openings on its three sides, people passing by can see soldiers sitting behind random barricades.

This is the Turkish Restaurant in the heart of Baghdad. Its front overlooks Tahrir Square and behind it is the fortified Green Zone. It stands high on the neck of the Jumhuriya Bridge from the side of Rusafa. The place is gloomy and evokes a feeling of fear when approaching it at night. One can no longer hear the noise and enthusiastic songs that came from it. Nor see the green laser lights that used to descend as sharp columns from its windows onto the protesters and the riot police.

Protest Center

For months, starting in October 2019, and continuing until the middle of the following year, the building known as the Turkish Restaurant was a key symbol of the popular protests that swept the cities of central and southern Iraq. A large Iraqi flag and slogans hung from it which expressed the aspirations and dreams of a new post-2003 generation who see no future as a result of corruption in state institutions and conflicts brought about by external influence in Iraqi affairs.

The 14-storey building was built in 1983. Iraqis named it after the Turkish restaurant that occupied its top floor. It had a panoramic design, and its walls were filled with pictures of rejected politicians, whose faces are marked with an X. However, the high-rise building also had a strategic dimension, in addition to the symbolism that these slogans and images provided. Protesters used it as a shelter and as a watchtower to monitor the movement of security forces as they progressed towards Tahrir Square.

When they later descended from “Uhud Mountain[1],” to avoid the security forces, they could not agree on the end. More than 800 demonstrators were killed and over 25,000 injured, in addition to hundreds of emigrants, out of fear of persecution. These angry youths achieved little of their goals other than the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi and his government, and the amendment of the election law. When the head of the intelligence service, Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, took over the formation of an interim government whose main task was to hold early elections, he began making promises to them as they were leaving the squares. In addition to his pledge to prosecute and hold accountable the killers of protesters and activists, whom the authorities referred to as third parties without specifying their identities, Al-Kadhemi dictated on November 12 that the Turkish restaurant would be transformed into a Tishreen Museum. “The October demonstrations are a lesson for us all. Your rights will not be lost,” he said, addressing the angry protesters. Some political parties considered him to be siding with the protesters at that time.

Al-Kadhemi’s office soon erected a sign on the building that read Tishreen Museum with the phrase “With the support and patronage of Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhemi.” According to the sign, the Prime Minister’s Office was responsible for supervising the museum’s work, and the name of Consultant Architect Saman Kamal” was also placed on the sign. Saman Asaad Kamal is known for his friendship and closeness to the Iraqi artist Ismail Fattah al-Turk. Their relationship saw work on one of Baghdad’s most important landmarks, the Martyr’s Monument.

In contrast to Kamal’s eagerness to talk about the various stages of completion with the Martyr’s Monument, his approach to the Tishreen Museum was devoid of enthusiasm. “The project is on hold,” he said. “I designed it, but it was not implemented for reasons that have nothing to do with me,” he added.

Like Kamal, several government institutions claim to not know about the museum’s fate, as the discussion about it was confined to the Prime Minister’s Office. Ahmed Al-Aliawi, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Culture, confirmed that they did not receive any instructions to turn the Turkish restaurant into a museum. He said that the Prime Minister “at the time assigned a committee to study this issue. A staff of engineers and architects was identified.” The Ministry of Culture had an idea to turn the building into a public art museum dedicating one of its floors to a memorial of the Tishreen demonstrations, but this was not achieved, according to Al-Aliawi. The Council of Ministers and its president, Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, are the sponsors of the museum project. As such, the Ministry of Culture does not have any details about it and what happened to it. The Municipality of Baghdad said that the project had not yet been approved by the Council of Ministers, and its spokesperson did not provide any details.

On August 23, 2021, Sabah Mashtat, Mustafa al-Kadhemi’s brother and advisor to some Iraqi media outlets, said that a legal problem had impeded the conversion of the Turkish restaurant into a museum. He stated that lawsuit had been claiming to be from the owner of the building with a previous investment license from the Baghdad Municipality. Mashtat said, “It is not possible to proceed with converting it into a museum without resolving the ownership problem.” However, an official source in the Supreme Judicial Council denied this was true in an interview with Jummar. Without using the diplomatic tone he is known for in the judiciary, he said, “The place is not governmental. There is no investment, there is no museum or anything like that. It is abandoned and neglected, and the harsh weather has destroyed the banner which was put in by the Prime Minister’s Office.”

Center of Power

In 2011, when Iraq also witnessed large-scale protests, the high-rise concrete building which had been abandoned since the occupation of Baghdad in April 2003, became the centre of operations to quash protests in Tahrir Square. Politicians and security commanders stood on the building’s balconies carrying communication devices to convey the situation to the centres of power. Surveillance cameras were installed at its corners, which facilitated the suppression and dispersal of angry gatherings.

For this reason, many of the new political groups that have emerged from the more recent protests believe that these parties, which have been deal with using a tight security grip, would never accept the building as a museum. The National Home Party “Al-Bait A-Wattani” is one of these movements. “The demands of the political and public uprising have not been fulfilled. It is too early to talk about the establishment of a museum that commemorates Tishreen because Tishreen has not ended,” Yasser Adnan, Deputy Secretary-General of the National Home Party, said.

Adnan believes that the museum represents “the government’s intention to convey an image that suggests the end of the October protests, that they have now become a thing of the past.” The problem is not, as he sees Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhemi, “who was not the candidate of the protesters. To say that his government is the product of the demonstrations is very false.”

“There are influential political parties who will try to distort history because it exposes them and reminds them of the ugliness and criminality of the political authority that ruled Iraq at the time. These parties are still from within this authority and will oppose such projects (i.e. the Tishreen Museum) and try to falsify and distort the history of the uprising.”

“The lack of interest by successive and current governments in the cultural aspects of the Iraqi heritage and the lack of buildings, institutions, edifices and museums befitting Iraq’s history, which is one of the oldest civilizations in the universe,” confirms the fate of the establishment of a museum for the October protests.

For him, “implementing the demands of the protests and working on legislative and legal reforms and all governmental and societal sectors” takes precedence over the establishment of the museum. “Tishreen does not need it to be immortalized. Many historians, writers and authors wrote about it. The Iraqi memory is not fragmented enough to forget what happened.” And if the building of the Turkish Restaurant must be converted into a museum, “the real protesters, protest movements, institutions and emerging parties emanating from the demonstrations must be involved in laying the foundations of the museum so as not to interpret or distort the course of the October protest, its history and goals.”

Meanwhile, MP Sajjad Salem said that “the period after (the October protests) should be a period of political struggle in order to achieve the values of the revolution.” The head of the Artists Syndicate, Jabbar Judy, presented a proposal for the building of the Turkish Restaurant. If the building were to be restored to its original condition, with a parking lot and a restaurant on the last floor, it will become a Baghdad landmark. Judy does not like the current museum plan. “What will the government put inside the museum to commemorate the October uprising? The blood of the martyrs or the gas canisters? What will they put in it?” he wondered. Judy said, “The October revolution was immortalized by social media and visual media, which has more than what the museum might include. We do not see any point in it.”

Absorbing the Anger

Sajjad Salem won a seat in Parliament during the elections of October 2021. Like most of his voters, Salem participated in the Tishreen demonstrations in Wasit Governorate, and became an independent representative of his governorate. He does not see the government being serious about turning the Turkish restaurant into a museum that will commemorate the protests. He accuses it of “launching the idea merely to absorb public anger following demands to perpetuate the revolution.” Salem describes the idea of the museum as good, in order “to witness a great mass uprising and remind future generations of its values, wounds, suffering, oppression and all of the tragic events that accompanied it.”

The Extension “Imtidad” movement also has a similar view. This political movement emerged from the protests and won 9 parliamentary seats in the last elections. Its spokesperson Rasoul al-Saray told Jummar that the movement was briefed on the project to convert the Turkish restaurant into a museum documenting the October protests. Al-Saray also sees the project as “a way to absorb the anger of the demonstrators at the time,” adding, “The government has not taken any step to implement it so far.’ He still supports his idea and considers it a “seed of freedom for future generations to learn (through the supposed museum) about the experiences of disassociation from the consequences of intellectual, ideological and factional misinformation.”

The building, he says, “forms, along with Tahrir Square, a spiritual shrine for citizens with all their ideas and ideologies. In it there is a serenity that captures the souls of passers-by, bearing memories of the birth of a homeland for which free people sacrificed hundreds of human sacrifices in order to flourish and grow up free.” However, he is apprehensive and believes that the idea of the museum could threaten the fate of any protests that might take place in the near future.

“Converting the Turkish restaurant into a museum will give future governments a guaranteed secure gate to the Green Zone. The government will have its hand in it plus a key to its treasury, and this will prevent it being used as a shelter or place to gather. It will also secure the main entrance to the government zone, and thus it will be a legalized and captured symbol for all subsequent government. “

The tone of the consultant engineer Saman Asaad Kemal Chi was curt when asked whether the Turkish restaurant building will remain deserted, “There is nothing new in the (museum) project…the project is on hold.”