Home Confinement in Iraq… Women Imprisoned by Society’s Ignorance

08 Mar 2023

How did families turn, with time, into gaolers, working for free for the establishment at the expense of their daughters’ happiness? Are we now completely indifferent towards them and unable to speak out or disobey society’s outdated traditions? Have we become so alien to them that we are capable of throwing our own flesh and blood underground in horrific, brutal sacrificial rituals only to please people and get their approval?

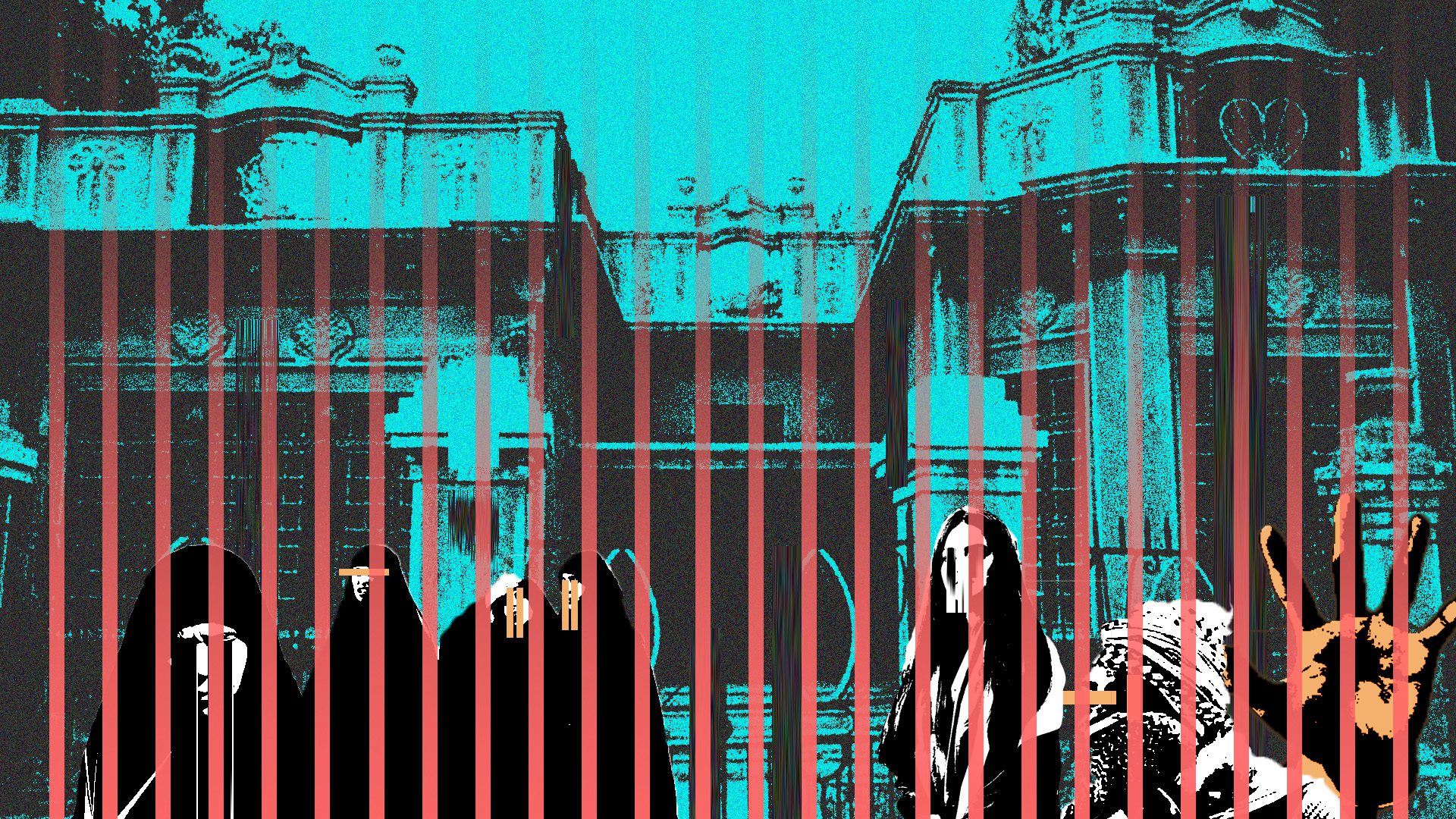

If men in Iraq have only one privilege, it is their freedom of movement, at least most of them. They usually have no restrictions that prevent them from moving freely, from their first steps as toddlers until their death. On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of Iraqi women and girls live in confinement, similar to the quarantine imposed during the Covid pandemic. Perhaps this is why women felt no change to their everyday lives, unlike men who were forced to stay home during the pandemic, albeit it temporarily, for health reasons. However, what did change for some women was their confinement with their male abusers in one house for longer than usual.

Quarantine for Iraqi women is a “normal” daily imposition, as they are prohibited from leaving the house without a series of approvals, justifications, and explanations that must be accepted as legitimate to the one who grants the exit permit.

Leaving the house is a right, and prohibiting it is an abuse!

“Forcible confinement”, “kidnapping”, or “violence” represent the denial of women’s basic human right –– to go out of the house. These are all descriptions of one act, which represents men’s desire to impose control and domination over the women in the family. Sometimes indirect relatives, such as grandfathers, uncles, or cousins, exercise their authority to prevent women from leaving home or deny them freedom of movement within the neighbourhood, city, or country. Any male relative can subject women in the family to imprisonment.

This practice falls under the definition of domestic violence. It is represented as economic violence that prevents women from engaging in education or work, besides being psychological and emotional violence by forcing them to cut off connections to these social institutions as well as to friends and family, which also undermines their feelings. Many of these prohibitive practices are accompanied by physical violence.

Although violence, specifically against women, is on the top of the agenda of human rights organisations in general and feminist organisations in particular, deprivation of going out or forcible confinement are not explicitly considered a form of violence. However, it is one of the most common forms of violence imposed on Iraqi women, as it is rare for any woman in Iraq to not have experience of it, to some extent.

For example, in its detailed report on gender equality and women’s empowerment in Iraq, Oxfam did not refer to forcible confinement as a form of violence as much as it considered it a determinant that prevents women from economic participation. It referred to what it called the man’s constant “insistence” on tracking women’s whereabouts and having to ask his permission to obtain health care!

This situation applies to many women, and it can actually be considered a form of abuse even though many in society consider it to be the right of men to limit or totally deny women’s freedom of movement. This crime is not limited to restricting movement, however, but also involves a whole set of consequences of this for women. It is believed that preventing women from going out only occurs when a woman wants to have fun -which is her right- but in fact, it extends to more serious cases, which results in financial or even material loss. Many have attempted to challenge this situation daily, but their attempts have not succeeded, except for older ladies who are considered to “be safe and have nothing to fear” due to their age, flabby bodies, and loss of youth!

F. A., now fifty-two, has been deprived of going out for much of her life. She was widowed at a young age, which was a justification for her husband’s family to prevent her from leaving home without the permission of her husband’s older brother, who lives far from them. If she did not comply, they would deprive her of her children as a punishment. This confinement prevented her from litigating a case concerning her inheritance and property, which made her lose part of her and her children’s money as she could not reach a lawyer.

Things got even worse as she lost her share of the inheritance when her brother-in-law prevented her from appointing a lawyer at court and instead brought her a fake lawyer to the house to sign over to him a special mandate. Later, she discovered that it was a general power of attorney for the brother-in-law to dispose of her and her children’s properties.

Female activists are also home-confined

This denial of freedom of movement applies to feminist activists as well, who defend Iraqi women’s rights. Despite holding important community positions, many of them cannot travel or stay for a few days in areas far from their homes, for work purposes, and of course, neither can they leave the country without a complicated series of approvals, guarantees, and justifications in negotiation with the men of the family.

In light of this reality, one must question the point of feminist work on women’s empowerment, promotion of political participation and democracy, involving women in society cohesion campaigns, and other activities of civil society organisations, while those who carry out all this work could be forcibly confined by any man in the family only because he is a man!

Feminist activist, A.H., considers herself lucky because her family, after a long struggle, allowed her to travel for an internship at the United Nations. However, she had to comply with their conditions of not leaving her hotel room after seven o’clock in the evening and taking pictures daily of her bedroom for them. A.H. says that her relationship with her family changed due to these conditions which demonstrated their suspicion and entailed for her a sense of humiliation, but above all, a feeling of helplessness.

As for N.S., an environmental activist, she obtained the right to go out gradually, with this taking her many years and stages. It became more difficult the more she rejected marriage proposals. She was able to move freely to some extent, thanks to her resistance and rational, calm conversations with her family. However, she could not maintain or protect this right due to an inappropriate comment on her Facebook page by an unknown account. She does not know if this account is real or fake, is a known or unknown person in society, a teenager or an adult but it changed her life and frustrated her, and she found herself going back to square one. But this did not stop her from pursuing her community work within “possible” limits, as she put it.

Forcible confinement as punishment

The crime of forcible confinement has enormous repercussions for all women, which naturally takes a toll on society as a whole. Women’s mental health and physical health are deteriorating due to a dull routine, lack of movement, scarcity of actual communication with the outside world, and having their daily activities monitored. This is in addition to the difficulty of obtaining a job that satisfies the family, if they allow their female members to work at all, which is usually replete with numerous conditions in the first place! All of this negatively impacts the family’s life, its coordination, and energy, which accompanies a woman even in the most prevailing trajectory, which is leaving her family’s home to her husband’s home.

As for girls, pre-marriage confinement means their inability to choose a life partner or even know them more before marriage, which could reduce the possibility of divorce resulting from a wrong choice. Then, another type of confinement is created. Although families and society cause incompatible marriages to recur, the law makes it hard for women to end a broken marriage.

This means that the crime of forcible confinement ultimately creates mothers in constant fear and apprehension as a result of the anticipation of surveillance, as their daily practices are constantly monitored to ensure they are aligned with societal standards, “accepted” by society, and adhere to patriarchal concepts completely. In conclusion, society reproduces the structures of domination with the involvement of mothers themselves.

Revolutionaries awaiting permission

Forcible confinement prevents women from breaking the cycle of ongoing violence, as it is the main reason for their inability to speak up against the patriarchal system and protest against it, through feminist demonstrations in public spaces. Despite all the anger that women express on social media in response to the killing, brutalisation, or mutilation of another woman, and their rage over legal articles that legitimise misogyny and accept it as a method of “dealing” with women, this anger does not reach the streets.

How do women ask permission to go out from those they want to protest against?

In the Tishreen [October] uprising in 2019, a significant number of women protested. It was their historic opportunity, and they lost it because they only called for the same national demands as men, which are mostly legitimate as long as they include civil liberties. The problem, however, was not fully realising the double oppression inflicted on them as citizens and as women.

For women, protesting required many measures of concealment, such as avoiding being photographed in demonstrations so that their families, who refused to let them out, did not see the pictures. They had to wear sunglasses and masks to hide their faces from those who might know them at the protests, as well as devising various creative excuses to persuade their families to let them go out. Meanwhile, men came en masse, in their cars, on public transport, or on foot to demonstrate, mostly without their families even questioning them.

Iraq’s modern history has rarely recorded massive demonstrations raising purely feminist demands. One of them, however, was the March of Roses in response to a religious leader calling for gender segregation in the 2019 protests. Even this one was in the context of the public demonstrations. As for demonstrations calling for purely feminist demands and rights, such as amending custody articles in the Personal Status Law of 1959 or demanding the enactment of a law criminalising violence in Iraq, they were completely inconsistent with the objections to these occurring on social media.

Women have many reasons for their inaction. Speaking about the vigils that took place after the killing of Taiba Al-Ali, Y.Y. says, “I am not even allowed to go outside the backyard of the house; how can I reach the vigils? Sneaking out would cause me a lot of problems and might jeopardise my education”.

“I cannot go out. Participating in protests is forbidden, especially the ones regarding women. If I violated these rules, I might be dead like Taiba”, says Z.A.

Another women, R.A., said, “unfortunately, they did not hold a mourning vigil (in my area), and even if they did, I would not have been able to attend because I am not allowed to leave the house without permission, and they (my family) do not allow me to participate in such events”.

M.A. says, “I engaged in everything online, but my father threatened me that if I stepped out of the door, I would have Taiba’s fate. I was forced to stay home and do nothing”.

There were several factors that caused outrage to prevail among women over the murder of Taiba Al-Ali on the pretext of an honour killing. Above all, it was the audio recordings of the victim negotiating to obtain her right to a safe life and to go out. Taiba wanted to be freed from living in confining conditions, which other women have been experiencing for years, but it was never called kidnapping or forcible confinement.

Negotiations are excessively repeated in our lives, hundreds of times, in order to obtain bits of our rights from a husband or a family member, just to try and make them understand our point of view. It is the hardest thing for anyone to try and explain what is already obvious, and argue to make one’s “opponents”, that is the family, see from a fair, unbiased angle that does not represent the interests and privileges of one side over the other.

How did families turn, with time, into gaolers working for free for the establishment and at the expense of their daughters’ happiness? Are we now completely indifferent towards them and unable to speak out or disobey society’s outdated traditions? Have we become so alien to them that we are capable of throwing our own flesh and blood underground in horrific, brutal sacrificial rituals only to please people and get their approval?

Many women and feminist groups mobilised for demonstrations that turned the authorities’ attention, even if it was only for once, towards women’s issues; yet the turnout was poor. This was shameful to those who mobilised the protests and ironic for whoever professed the weakness of the feminist movement on the ground. Many female activists who couldn’t attend, did not speak out about being forcibly confined and unable to move anywhere without permission. Their embarrassed silence could be because of their academic, professional, or societal status. Forcible confinement, however, remains a key issue for our current feminist movement. As primary and secondary education was the central cause for the first generation of Iraqi feminists in the last century, we are yet to move any further, and we are still imprisoned by society’s ignorance.

Read More

If men in Iraq have only one privilege, it is their freedom of movement, at least most of them. They usually have no restrictions that prevent them from moving freely, from their first steps as toddlers until their death. On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of Iraqi women and girls live in confinement, similar to the quarantine imposed during the Covid pandemic. Perhaps this is why women felt no change to their everyday lives, unlike men who were forced to stay home during the pandemic, albeit it temporarily, for health reasons. However, what did change for some women was their confinement with their male abusers in one house for longer than usual.

Quarantine for Iraqi women is a “normal” daily imposition, as they are prohibited from leaving the house without a series of approvals, justifications, and explanations that must be accepted as legitimate to the one who grants the exit permit.

Leaving the house is a right, and prohibiting it is an abuse!

“Forcible confinement”, “kidnapping”, or “violence” represent the denial of women’s basic human right –– to go out of the house. These are all descriptions of one act, which represents men’s desire to impose control and domination over the women in the family. Sometimes indirect relatives, such as grandfathers, uncles, or cousins, exercise their authority to prevent women from leaving home or deny them freedom of movement within the neighbourhood, city, or country. Any male relative can subject women in the family to imprisonment.

This practice falls under the definition of domestic violence. It is represented as economic violence that prevents women from engaging in education or work, besides being psychological and emotional violence by forcing them to cut off connections to these social institutions as well as to friends and family, which also undermines their feelings. Many of these prohibitive practices are accompanied by physical violence.

Although violence, specifically against women, is on the top of the agenda of human rights organisations in general and feminist organisations in particular, deprivation of going out or forcible confinement are not explicitly considered a form of violence. However, it is one of the most common forms of violence imposed on Iraqi women, as it is rare for any woman in Iraq to not have experience of it, to some extent.

For example, in its detailed report on gender equality and women’s empowerment in Iraq, Oxfam did not refer to forcible confinement as a form of violence as much as it considered it a determinant that prevents women from economic participation. It referred to what it called the man’s constant “insistence” on tracking women’s whereabouts and having to ask his permission to obtain health care!

This situation applies to many women, and it can actually be considered a form of abuse even though many in society consider it to be the right of men to limit or totally deny women’s freedom of movement. This crime is not limited to restricting movement, however, but also involves a whole set of consequences of this for women. It is believed that preventing women from going out only occurs when a woman wants to have fun -which is her right- but in fact, it extends to more serious cases, which results in financial or even material loss. Many have attempted to challenge this situation daily, but their attempts have not succeeded, except for older ladies who are considered to “be safe and have nothing to fear” due to their age, flabby bodies, and loss of youth!

F. A., now fifty-two, has been deprived of going out for much of her life. She was widowed at a young age, which was a justification for her husband’s family to prevent her from leaving home without the permission of her husband’s older brother, who lives far from them. If she did not comply, they would deprive her of her children as a punishment. This confinement prevented her from litigating a case concerning her inheritance and property, which made her lose part of her and her children’s money as she could not reach a lawyer.

Things got even worse as she lost her share of the inheritance when her brother-in-law prevented her from appointing a lawyer at court and instead brought her a fake lawyer to the house to sign over to him a special mandate. Later, she discovered that it was a general power of attorney for the brother-in-law to dispose of her and her children’s properties.

Female activists are also home-confined

This denial of freedom of movement applies to feminist activists as well, who defend Iraqi women’s rights. Despite holding important community positions, many of them cannot travel or stay for a few days in areas far from their homes, for work purposes, and of course, neither can they leave the country without a complicated series of approvals, guarantees, and justifications in negotiation with the men of the family.

In light of this reality, one must question the point of feminist work on women’s empowerment, promotion of political participation and democracy, involving women in society cohesion campaigns, and other activities of civil society organisations, while those who carry out all this work could be forcibly confined by any man in the family only because he is a man!

Feminist activist, A.H., considers herself lucky because her family, after a long struggle, allowed her to travel for an internship at the United Nations. However, she had to comply with their conditions of not leaving her hotel room after seven o’clock in the evening and taking pictures daily of her bedroom for them. A.H. says that her relationship with her family changed due to these conditions which demonstrated their suspicion and entailed for her a sense of humiliation, but above all, a feeling of helplessness.

As for N.S., an environmental activist, she obtained the right to go out gradually, with this taking her many years and stages. It became more difficult the more she rejected marriage proposals. She was able to move freely to some extent, thanks to her resistance and rational, calm conversations with her family. However, she could not maintain or protect this right due to an inappropriate comment on her Facebook page by an unknown account. She does not know if this account is real or fake, is a known or unknown person in society, a teenager or an adult but it changed her life and frustrated her, and she found herself going back to square one. But this did not stop her from pursuing her community work within “possible” limits, as she put it.

Forcible confinement as punishment

The crime of forcible confinement has enormous repercussions for all women, which naturally takes a toll on society as a whole. Women’s mental health and physical health are deteriorating due to a dull routine, lack of movement, scarcity of actual communication with the outside world, and having their daily activities monitored. This is in addition to the difficulty of obtaining a job that satisfies the family, if they allow their female members to work at all, which is usually replete with numerous conditions in the first place! All of this negatively impacts the family’s life, its coordination, and energy, which accompanies a woman even in the most prevailing trajectory, which is leaving her family’s home to her husband’s home.

As for girls, pre-marriage confinement means their inability to choose a life partner or even know them more before marriage, which could reduce the possibility of divorce resulting from a wrong choice. Then, another type of confinement is created. Although families and society cause incompatible marriages to recur, the law makes it hard for women to end a broken marriage.

This means that the crime of forcible confinement ultimately creates mothers in constant fear and apprehension as a result of the anticipation of surveillance, as their daily practices are constantly monitored to ensure they are aligned with societal standards, “accepted” by society, and adhere to patriarchal concepts completely. In conclusion, society reproduces the structures of domination with the involvement of mothers themselves.

Revolutionaries awaiting permission

Forcible confinement prevents women from breaking the cycle of ongoing violence, as it is the main reason for their inability to speak up against the patriarchal system and protest against it, through feminist demonstrations in public spaces. Despite all the anger that women express on social media in response to the killing, brutalisation, or mutilation of another woman, and their rage over legal articles that legitimise misogyny and accept it as a method of “dealing” with women, this anger does not reach the streets.

How do women ask permission to go out from those they want to protest against?

In the Tishreen [October] uprising in 2019, a significant number of women protested. It was their historic opportunity, and they lost it because they only called for the same national demands as men, which are mostly legitimate as long as they include civil liberties. The problem, however, was not fully realising the double oppression inflicted on them as citizens and as women.

For women, protesting required many measures of concealment, such as avoiding being photographed in demonstrations so that their families, who refused to let them out, did not see the pictures. They had to wear sunglasses and masks to hide their faces from those who might know them at the protests, as well as devising various creative excuses to persuade their families to let them go out. Meanwhile, men came en masse, in their cars, on public transport, or on foot to demonstrate, mostly without their families even questioning them.

Iraq’s modern history has rarely recorded massive demonstrations raising purely feminist demands. One of them, however, was the March of Roses in response to a religious leader calling for gender segregation in the 2019 protests. Even this one was in the context of the public demonstrations. As for demonstrations calling for purely feminist demands and rights, such as amending custody articles in the Personal Status Law of 1959 or demanding the enactment of a law criminalising violence in Iraq, they were completely inconsistent with the objections to these occurring on social media.

Women have many reasons for their inaction. Speaking about the vigils that took place after the killing of Taiba Al-Ali, Y.Y. says, “I am not even allowed to go outside the backyard of the house; how can I reach the vigils? Sneaking out would cause me a lot of problems and might jeopardise my education”.

“I cannot go out. Participating in protests is forbidden, especially the ones regarding women. If I violated these rules, I might be dead like Taiba”, says Z.A.

Another women, R.A., said, “unfortunately, they did not hold a mourning vigil (in my area), and even if they did, I would not have been able to attend because I am not allowed to leave the house without permission, and they (my family) do not allow me to participate in such events”.

M.A. says, “I engaged in everything online, but my father threatened me that if I stepped out of the door, I would have Taiba’s fate. I was forced to stay home and do nothing”.

There were several factors that caused outrage to prevail among women over the murder of Taiba Al-Ali on the pretext of an honour killing. Above all, it was the audio recordings of the victim negotiating to obtain her right to a safe life and to go out. Taiba wanted to be freed from living in confining conditions, which other women have been experiencing for years, but it was never called kidnapping or forcible confinement.

Negotiations are excessively repeated in our lives, hundreds of times, in order to obtain bits of our rights from a husband or a family member, just to try and make them understand our point of view. It is the hardest thing for anyone to try and explain what is already obvious, and argue to make one’s “opponents”, that is the family, see from a fair, unbiased angle that does not represent the interests and privileges of one side over the other.

How did families turn, with time, into gaolers working for free for the establishment and at the expense of their daughters’ happiness? Are we now completely indifferent towards them and unable to speak out or disobey society’s outdated traditions? Have we become so alien to them that we are capable of throwing our own flesh and blood underground in horrific, brutal sacrificial rituals only to please people and get their approval?

Many women and feminist groups mobilised for demonstrations that turned the authorities’ attention, even if it was only for once, towards women’s issues; yet the turnout was poor. This was shameful to those who mobilised the protests and ironic for whoever professed the weakness of the feminist movement on the ground. Many female activists who couldn’t attend, did not speak out about being forcibly confined and unable to move anywhere without permission. Their embarrassed silence could be because of their academic, professional, or societal status. Forcible confinement, however, remains a key issue for our current feminist movement. As primary and secondary education was the central cause for the first generation of Iraqi feminists in the last century, we are yet to move any further, and we are still imprisoned by society’s ignorance.